Unplanned obsolescence

A meandering "essay" on literary careerism, sensibility, style, & selling out

“More than realism or its rivals, the dominant literary style in America is careerism,” so begins Christian Lorentzen’s 2021 review of a Philip Roth biography in Bookforum. Call it what you will: selling out, clout chasing, having “a public career,” maintaining a meticulously controlled brand, cultivating an online persona, being a literary it girl. This diagnosis now applies to every creative industry and, like Lorentzen, I don’t mean it as a judgment or a slur. But the word “careerism” sounds somewhat outdated today, as it implies that there is still a career to be had, an institutional ladder to climb, worthy gatekeepers to please. As venerated institutions lose their cultural status and legitimacy, trading money for morals, disintegrating like a billboard whose colors have been washed out by the sun, careerism has acquired the worn sheen of a decades-old denomination with dwindling, nevertheless fervent practitioners.

After reading Dirt’s latest series of articles, published in collaboration with LitHub, I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time this past week thinking about literary careerism — that is, the ability to financially sustain oneself via book sales, grants, awards, and prestigious teaching gigs. Such a vocation is only attainable for a select few, namely for those who come from money, publish the rare bestseller, and/or attend elite programs and universities. Even so, as David Hill admits in his essay “Writing as Labor,” “the concept of a writer that [most people hold] in our collective consciousness was a myth, a cultural construction informed by a small number of relatively famous writers. The truth is, few people can earn a full time living simply writing books.” Careerism is a dream dead upon arrival, and this was true in the 1980s as it is today. A one-time deposit of $50,000 for a Guggenheim Fellowship is a tough sum to live on for a year in any major metropolitan area. It was refreshing to read about how the poet Alice Notley and her late husband Ted Berrigan spent their 1979 NEA grants “really fast because [they’d] never had any money before.”

In any case, everyone not on the careerist track settles for selling out to sustain artistic production — though perhaps “selling out” is not quite the right phrase. In the capitalist marketplace, we are all selling something in the trade-off for more leisure time. This material sustenance now also involves chasing clout, social associations that help one feel relevant, good, important, or desired. If “having lots of money confers status but having very little confers legitimacy, which offers a different kind of status,” as Emily Cooke writes in a 2017 Bookforum piece on wealth and class in the literary world, clout (or “community,” as some prefer to call it) can be a kind of equalizer, an alternative ladder to ascend.

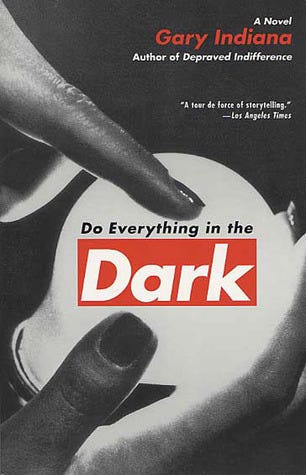

I recently finished Do Everything In The Dark, Gary Indiana’s turn-of-the-millennium novel about the downtown demimonde. The characters are all clout chasers through and through, and Indiana’s biting cynicism towards their antics is infectious. A little over halfway through the novel, the narrator speaks of how “something vile was taking course” in the zeitgeist. People were “drap[ing] themselves in product logos and designer alphabets, like free-ranging billboards … like serfs declaring fealty to corporate gods.” The narrator, an obvious proxy for Indiana, was staring at passersby on Astor Place in disgust, something he likely did on lunch break at the Village Voice. “Did I really want to scream into those moist rodent faces, HOW FUCKING SOLD OUT CAN YOU BE? IS IT A COMPETITION?” Indiana’s proclivity for peppering his prose with petty and barbarous jibes makes for a satisfying read, but underneath every character’s smug, self-centered smile is a deep well of melancholy. Their curdling visage betrays the fear of irrelevancy that comes with aging, of the dead-end realization that the good times have gone, possibly forever. Do Everything In The Dark is set in 2001 New York but the messy and incestuous social dynamics between Indiana’s reputation-obsessed characters feel as relevant as ever. Except now, selling out is a given, an act not even worth castigating. People either think, “Oh, this person is already rich.” Or, “Good for them, they secured the bag.” At least in the arts, I don’t think we can honestly characterize selling out as a conspicuous act but a contemporary sensibility entrenched in the brine of late capitalism that we all swim in. A reflex of our social system and its economic structures.

In her essay “Subculture,” published in Artless: Stories 2019-2023, Natasha Stagg writes,

“In the hustle economy, everyone becomes their own product, and this tramples an already sputtering underground, luring even the most subterranean of content creators to its neoliberal landscape. The contrarian, the politically incorrect, and the avant-garde are celebrated, platformed for all they’re worth … Once we all stepped into the pinball game of the social network, selling out became an obsolete concept.”

I’m interested in Stagg’s use of the term “obsolete” here, which recalls the phrase “planned obsolescence,” that pesky, unavoidable feature built into consumer electronics. Selling out, to Stagg’s point, became an obsolete concept because it was unavoidable, a natural feature of networked life. In his review of Artless, James Duesterberg wonders whether the aforementioned passage is an original thought or a line Stagg is simply repeating: “The point is that we can’t say: what has gone missing is precisely any distance between subculture and marketplace, or artist and worker. This is the state of things to which Stagg’s ‘uncareful’ style quite carefully testifies. When everything is media, art can no longer mediate: and this is simultaneously an artistic problem and a broader, social and political one.”

This overlap between subculture and marketplace is something that I’ve been blindly grasping at in my writing on trends and aesthetics, though I haven’t encountered much criticism on contemporary literature that frames it along these explicit terms, probably because writers are profoundly uncomfortable with thinking about publishing as a market, a market that yields, as Dan Sinykin explores in Big Fiction, a certain style of writing and a certain artistic sensibility. Indeed, sensibility1 can be more difficult to discern than style, although the two are closely intertwined. Contemporary writers signal their sensibilities through the affect, identity, and politics of their characters, adopting a posture of self-awareness or externalized (almost automatic) observation that seeps into the tone/style of fiction and narrative nonfiction alike.

Duesterberg’s assessment of “millennial autofiction,” for example, finds that the narrators are studied and self-conscious to an irksome degree. Of writers like Lauren Oyler, Ben Lerner, Sally Rooney, and Patricia Lockwood, he says: “The writing has lost its ironic edge and acquired the bland, studious distance of celebrity endorsements and propaganda. This is, above all, the writing of someone who is being watched: someone who knows exactly what they are sending out, and who is receiving it. The fantasy of artistic autonomy is no longer even conceivable to these narrators—has become “obsolete.” And without it, the drama of the autofictional voice, its tension between irony and complicity, loses narrative purchase. In a world already saturated with text, a world in which language’s illusive power seems to function all by itself, the artist-narrator becomes, simply, a conduit of the discourse.”

I haven’t read Fake Accounts and only snippets of No Judgement but curiously, that’s exactly the indictment Ann Manov offers of Oyler’s latest essay collection — that it is obsessed with coming across as “highbrow” despite the flimsy research and dated topics. But to bring it back to litfic, there’s a clear industry preference for realism, relatable subject matter (romance, divorce, boring and bad jobs, family life), and naturalistic, straightforward prose. The oft-debated notion of protagonist “likability” further emphasizes how novels increasingly serve to mediate a kind of aggregate identity conflation, as the reader, narrator, and writer become synergistic conduits of/for online discourse.

I don’t want to get stuck talking about the Millennial Novel or those “wan little husks” of autofiction but I recently read Brandon Taylor’s latest LRB piece on Zola and returned to his (better and shorter) 2021 Substack post, which argues that contemporary millennial novels are Naturalist constructions, some explicitly more so than others. These books are vaporous, per Taylor’s description: “What matters are the vibes. Reading a Millennial Novel feels like listening to songs from your middle school dance on Spotify. The emotional recall is intense. Immediate. But then you realize, oh, that’s not the song. That’s the song that sounds like the song … And what frustrations we have with the Millennial Novel — the inertness of its characters, the lack of warmth, the lack of transcendence, the stiff, scathing Hopper-esque moral attitude — all flow from the same frustrations we had with Naturalism.”

In the March issue of the NYRB, Merve Emre presented a more persuasive argument on Rooney’s behalf, arguing that in Beautiful World Where Are You, the novelist “troubles certain received and, indeed, narcissistic ideas about what a fictional character ought to be. A character, many insist, should be an individual like us, a person whose surfaces may be encrusted with the cultural detritus of the present but whose depths are sanctified by complexity, by a sense of mystery, and by that venerable shibboleth, personality.” In other words, Rooney is refusing to write a “three-dimensional” character because she’s rejecting the readerly expectation of what a character should be. Conceptually, I get it. But does that make the book good or interesting to read? BWWAY is an epistolary-style novel that alternates between chapters of email correspondence and chapters written from a distant third-person remove with minute descriptions of the characters’ actions, akin to action lines in a script. According to Emre, “The game played by Rooney and novelists like her is a supremely intelligent critique of our discourse, not a symptom of its sanctimony.” But again, I have my doubts about what this meta-level of discourse can do. It certainly doesn’t enlighten or delight me as a reader. Is the point of art to be a critique of the discourse? Or to replicate a mood/mode of realism that feels real but isn’t — “the song that sounds like the song” but isn’t really the song? What is the point of that?

In fashion, art, literature, etc, we’re past the point where there’s a dominating aesthetic “school,” so a common reflex is to borrow old terms (ie Romanticism, Realism) used to define a different time period’s stylistic tics and graft it onto a contemporary work or artist. Call this the moodboard-ification of everything. We have at our fingertips a trove of historical/aesthetic inspiration. But unlike in certain visual mediums, where you can point at X, Y, and Z to prove that this filmmaker was inspired by Hitchcock or Kubrick or whomever, writerly influence is less capable of simple discernment. This is all to say that I’m not quite as convinced that writers are simply returning to Realism, as much as what’s being produced is a flimsy copy of realism. The shift from modernism to postmodernism is often thought of as a return to realism and figuration after abstraction. We appear to be still in that representational mode, down to the way people talk about “feeling seen” or represented through certain fictional characters and stories. The philosopher Frederic Jamison, however, argues that perhaps postmodernism is “not really figurative in any meaningful realist sense,” as it is “a realism of the image rather than of the object and has more to do with the transformation of the figure into a logo than with the conquest of new ‘realistic’ and representational language. It is thus a realism of image or spectacle society, if you will, and a symptom of the very system it represents in the first place.”

And so, I guess we return to clout — the “spectacle society” of associations that inform literary culture on the internet. How are we to write characters — or even ourselves — when our ways of knowing people have become both personalized and impersonal, our affect increasingly determined and mediated by the virtual? I particularly liked this passage from Emre: “How to derive specific types when individuals in the world appear as both anonymous and conspicuous, opaque and transparent, strange and intimate, fictional and factual?” This has complicated our understanding of character as a whole, this transformation of the figure into a logo, a brand. But the extent to which literature has tried to address this is through internet/influencer novels, which are quite realist, feels lacking. Now I get why Taylor is so keen on denying physicality in the Millennial Novel; it’s easier to opt for vibes instead. A fleeting feeling. An idea of a person, a shadow of them through the screen…. 2

In Do Everything In The Dark, one character tells another: “We should all burn our dummies when they don’t support our delusions anymore.” The context of the quote is quite sad, but don’t worry, I won’t spoil it. I loved this quote so much I wrote it in two different notebooks and took a picture of the page. I guess I am trying to get rid of some delusions, but I am keeping my dummies. I suppose our characters/personas are a kind of dummy for us to enact certain fictions upon. Granted, if our online personas are our dummies, no one seems to want to hang up the old coat of delusions in the closet. What else will keep us warm?

In early April, two writers got into a brief Twitter tussle over a difference in, I suppose, sensibility. It began with a thread from one writer boasting that she had 50 literary publications in the past year — a rate I don’t think I ever achieved, not even when I was working in digital media. The other was fairly side-eyeing this claim in a series of subtweets. This inevitably boiled over into ad hominem attacks. The second writer, who I found myself agreeing with more, ended up deleting the various tweets that brought on the altercation and going private, but the situation emphasized how achievement-oriented today’s literary culture is, even among those who are staunchly not in the careerist camp. The struggle, after all, offers a sense of self.

I remember once scrolling past a Twitter thread from a writer who made a point of tallying their rejections every year. This is, as I’ve come to learn, a common practice. This writer made it a goal to have at least 50 to 100 rejections per year. It was, as they explained, a number’s game — the more you submit, the likelier your odds are for publication and, of course, rejection. To speak of rejection as a kind of negative achievement, as proof of growth, is incredibly depressing. (Per Byung Chul-Han in his book The Burnout Society: “The achievement subject gives himself over to compulsive freedom — that is, to the free constraint of maximizing achievement.”) I remember thinking how stupid, until my rejections started to significantly outpace my accepted submissions. Then I realized that perhaps this was the wrong way to go about being a writer: Seeking publication as literary validation and value becomes a distraction from the act of writing itself. To think of art in this way threatens to debase it into commodity, although I am not naive to think that the two can ever exist in separate spheres, nor that, as an artist, being bad at business is a virtue, as if that’s proof of one’s anti-capitalist convictions.

In a recent Paris Review essay, Tony Tulathimutte writes of the rejection plot, a second-rate story that is “all buildup and no closure, an inherent letdown.” The heartbreak of rejection is not loss. Rather, “the lack of happening is the tragedy.” The story stalls even as it continues, like a car in gridlock traffic. Tulathimutte’s essay addresses rejection in a romantic context but I find parts of it applicable to rejection in a literary context. “Love, we must repeat, is a matter of taste, and so cannot be disputed,” Tulathimutte writes. But there is a way forward in the rejection plot: “to reject rejection, through sheer gumption or delusion.” Indeed, writing is also a matter of taste, although the market’s preferred literary tastes are always up for dispute. And artistic persistence depends on one’s insistence on rejecting rejection. I believe rejection should be the writer’s natural habitat — not just the critic’s. Rejection as both a critical posture and an outlook. Rejection, when it’s not blindly celebrated as negative achievement, can be an affirmation of distinction — that the work is too zany, weird, unsellable. Or maybe it’s just underdeveloped and bad. Who knows. If there is increasingly little difference between the subculture and the marketplace, I wonder if rejection can service as a kind of bellwether for whatever hope there’s left for the literary avant-garde; if we can think of rejection as not achievement or obstacle but some secret third thing (lol)

Anyway, Tulathimutte’s quote on delusion reminds me of one of my favorite scenes in Do Everything In The Dark, after an encounter between the narrator and his ex-lover, Miles. It’s one of those few moments in the novel where Indiana earnestly employs the first-person at length to convey the narrator’s searing sentimentality for a man who has, in short, abandoned him. What he loves about Miles is his “obstinate refusal of reality. Not denial. Refusal. Even his refusal of the reality of failure, its weights and implications, was reason enough to love him. Miles saw that in a place where all the peaks were third-rate successes, failure could be a kind of beatitude.”

I am currently reading Joy Williams’ Breaking and Entering, an ‘80s novel about a drifter couple that breaks into people’s vacations home along the coast of Florida. Williams has taken a sharply allegorical/spiritual twist in her later work, but Breaking and Entering contains prime examples of the kind of glib, perfunctory dialogue that I encounter in alt-lit mags of the past five years. Like when I was reading Madeline Cash’s Earth Angel, I was thinking: Okay, this is trying to sound like Joy Williams but it’s doing a poor imitation of it. Williams isn’t a glib or perfunctory writer, by any means. She has a knack for having her characters say extremely weird, dark, digressive stuff, but it all ties together, it fits the novel’s Gothic mood.

Let me pitch a secret third thing lol: literary rejections can also be collected as some sort of utilitarian practice--building up (then maintaining) the finger calluses 'required' to play guitar without pain. They don't have to signify anything we want or don't want them to.

Hm actually another use might be as 'echolocation' to feel out 'the literary landscape' and one's place within it. Getting nothing but acceptances...that feels gross to me. My compass would get wonky so fast.

That Gary Indiana book sounds very interesting. Will put it on my to-read list, thanks.

Coincidentally, I just read this other Substack piece that comments on some writers who are still sad yet having achieved some monumental careerist goals (novel published, gotten big advance, etc.): https://theleftovers.substack.com/p/the-sadness-of-the-published-author?utm_source=profile&utm_medium=reader2

I guess the chase never ends.

I invented this hypothetical in my head a while ago, about if I could get a book published, but it would have to be under a pseudonym and nobody would ever know it was me and I myself would never get credit, would I still be happy? For those writers who can say yes, they're in the best place mentally because it's all about the work. It's not about wanting to be popular (at last!) or validated or any of the scene-related things that Freddie deBoer wrote about in his piece, "The Party's Over."