THE DIGEST

*starred content is mentioned below…

Books: The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy; The Dud Avocado by Elaine Dundy; The Language of New Media by Lev Manovich*; Prostitute Laundry by Charlotte Shane

Essays & Articles: “Art Today,” a 2006 lecture by Jean-Luc Nancy*; “E Pluribus Unum”* and “David Lynch Keeps His Head” by David Foster Wallace; “The Pain Artist” by Ben Lerner (NYRB)

Podcasts: Adam Phillips’ “Against Self-Criticism” on the LRB Podcast; Pace Gallery’s Arne Glimcher on Agnes Martin* (Art World podcast)

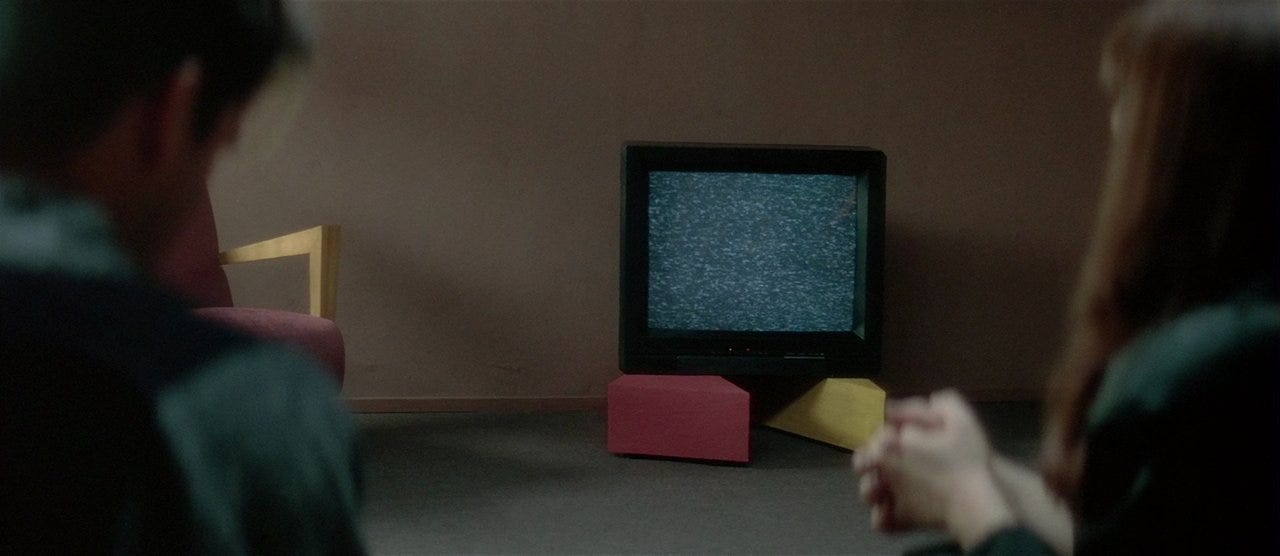

Movies: Lost Highway (1997) by David Lynch; Possession (1981) by Andrzej Zulawski; Vertigo (1958) by Alfred Hitchcock

Music: Rachmaninoff Concerto No. 2*

HOUSEKEEPING

It’s been nearly five years since I’ve published this newsletter. My career and my writing life have vastly changed since 2019, and I’ve started to feel that gen yeet is no longer the right name for my project on here… It remains to be seen whether a full rebrand is on the horizon, but I welcome any opinions and letters to the editor (terrygtnguyen@gmail.com) on newsletter rebrands, potential names, subjects for coverage, etc etc

In February, I’ll be publishing free short-form reviews every week that begin with a content digest up top. Twice monthly, paid subscribers will receive a meandering perspicacious post, comprised mostly of notes and commentary on my obsessions and what I’m close-reading/watching (similar in format to today’s newsletter).

1. Oh Rachmaninoff!

As I am writing this, I am on my fortieth listen of Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 2 in C Minor. Since mid-December, I have listened to Rach 2 at least once a day. I play it while doing yoga in the morning, while running errands, while cooking, while working. My newfound love for Rachmaninoff is surprising: I do not consider myself a classical music connoisseur. I would, in fact, consider myself a classical music ignoramus. After a decade of piano-playing (from ages 6 to 16), I’d decent enough finger dexterity to play a repertoire of classical compositions (Chopin, Beethoven, Bach, Mozart), albeit with poor interpretive skills and zero knowledge of music theory. It was clear early on that I was no prodigy. Nevertheless I played what was given to me by my teachers, picked up participation trophies, and, by a certain age, started to resent the repetitious practice required of me, a repetitious practice that I had no patience for and was forced to endure (I wanted to quit by my fifth year). And so for years afterward, I studiously avoided listening to any classical music, since the compositions, by no fault of their own, stoked in me a deep shame, and I disguised my aversion as a matter of taste…

This year, I resolved to spend more time close-reading, close-watching, and close-listening. A lot of time is required to close-read a book or close-watch a movie (more on those later), so I decided to start with music: Rach 2, a composition that I did not appreciate until I heard it scored on Brief Encounter (1945). The concerto begins with stilted trepidation—I have been listening to Yuja Wang’s recording with the LA Philharmonic—that swells into a formidable, climactic frenzy. Then, the melody slows into the adagio (my favorite part), sweetening into a familiar caress that is passed between the piano and the strings, before the orchestra entirely fades out for the piano to linger, almost forlornly, like the last person on an empty dance floor. The third movement, which I’m always inclined to skip, is a triumphant, thumping conclusion in C major.

It took about two weeks before I noticed the Rach 2 motif wedging itself into my subconscious. At random moments during the day, certain sequences would surface, as if my mind’s record player had suddenly turned on, and I’d hum them aloud, off-tune, marveling at how I could so easily recall Rachmaninoff’s “contiguous phrases.”

While walking through SoHo one day, I realized that the legato chord progression at the end of second movement strongly resembled “Laura Palmer’s Theme” from Twin Peaks. A quick Google search revealed that my suspicions had some basis, though not entirely correct: Twin Peaks composer Angelo Badalamenti was sued by the Rachmaninoff estate over three notes in “Laura Palmer’s Theme” that were found in Rach’s Prelude in C-Sharp Minor, a different piano composition in the same key.

The point of close-listening, for me, is discovery. I’m not sure exactly what I hope to discover or if there’s anything at all to “get.” This is the antithesis of the interpretive close-reading/watching/listening I was taught in high school, which treated the experience of art like a scavenger hunt, as if metaphorical deconstruction was the key to “understanding” art and gleaning the writer’s true intent. In any case, close-listening to Rach 2 felt a lot like a surrendering. To sit and let the aural landscape pass through me without expectation; to become so keenly aware of time (and life!) slipping on by; to realize that the experience of listening to Rach 2 for the first time can never be recovered.

I finally understood what John Ashbery meant when he wrote, “All art aspires towards the condition of music.” Music is, he argues, unique in its ability to transcend thought and critical analysis; the conditions for its enjoyment are predicated on a preternatural passivity. (Reading or watching a movie, on the contrary, requires active attention from its audience.) The listener becomes enraptured in the composition as a whole, and does not single out certain notes or sections as being “better” than the rest.

“We have talked to each other,

Taken each thing only just so far,

But in the right order, so it is music,

Or something close to music, telling from afar.”

“Life as a Book That Has Been Put Down,” John Ashbery

2. Form and Other Matters

Last week, I attended a talk with the psychotherapist Esther Perel on “realistic love.” A lot of what Perel discussed would be familiar to readers of her Mating in Captivity, but I keep returning to the response she gave to a frazzled twenty-something, who was fretting over the fact that marriage meant having to be fine with, and I quote, the “same dick forever.” Perel: “Sex is not something you do, it is somewhere you go.”

I nearly gasped when I heard this. Sex is not something you do, it is somewhere you go. We listen to our favorite songs over and over and over again without tiring of the melody; we hear and feel something new or different every time. Why does that thinking not apply to our relationships, our sex lives? Substitute art for sex and the sentiment still stands.

In his 2006 lecture on contemporary art, the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy says that good art “opens other possibilities of worlds,” such that every artist is a world unto themselves. (One can also argue that the best relationships, romantic or platonic, open up to us other possibilities of worlds. People have affairs, Perel said, because it makes them feel alive or even different; the introduction of a new person, a third, so to speak, reveals to them a new version of themselves, another world of possibility.)

This feels especially true with the painter Agnes Martin, who is the subject of a critical essay I’m thinking through. Martin’s minimalist works nearly defy description in their ineffable simplicity (Pace’s Arne Glimcher said that, while Martin was alive, she specifically did not want her works to be verbally described or contextualized in exhibition catalogs or to potential buyers); the essay grapples with the limits of language and ekphrastic poetry when confronted with works that are so “speechless,” blank, and spare. But in spite of that, Martin’s paintings have been the subject of much writerly interest, in part because her work demands — and rewards — close observation. When asked how long people should look at her canvas, Martin responded “a minute.” A minute at least, I would venture. A minute isn’t a long time at all — a photographer friend visiting New York recently spent three hours looking at one An-My Lê photo at MoMA — but I wonder what a minute versus an hour reveals in front of one of Martin’s grids.

One of Nancy’s greatest disappointments with contemporary art is that works can be too didactic, too explicit in meaning: “I see works that shoot a big block of significations at me, which say to me, ‘Here you are, this is war.’ … Yes, there is form in these works, but a message precedes it and dominates it.” Remarked in 2006, this still seems true today. Stefan Brüggemann’s winter show at Hauser and Wirth in LA is one example of how oversaturated messaging degrades any potential for form: Its centerpiece was a sign in neon red, white, and blue with the words TRUTH and LIE. Gold-leaf coated canvases spray-painted with keywords like CNN, DOMESTIC TERROR, OPTIMISTIC. An unintelligible blob of words that, despite their unintelligibility, still demand to be read. Perhaps we’ve taken too literally, “The medium is the message.” Form becomes an afterthought when content is what the audience is trained to look for. When the gesture is so obvious, why bother reading or looking closely?

From my Notes app: Esther Perel: “You have to look at the form and not the content” on her method of couple’s therapy. Most therapists focus on the content, the story/narrative that couples come in with and are intent on discussing. But the key to understanding a couple’s dynamic lies in the form of their interactions, not the story they purport to know about themselves.

3. Database Logic

I spent part of last week working on a piece about generative art and algorithmic curation, when I came across a passage from Lev Manovich’s The Language of New Media (2001) that convinced me to immediately buy the book. It had to do with Manovich’s notion of database logic:

“Many new media objects do not tell stories; they do not have a beginning or end; in fact, they do not have any development, thematically, formally, or otherwise that would organize their elements into a sequence. Instead, they are collections of individual items, with every item possessing the same significance as any other.”

This stands in contrast with “old” forms of media, like the novel or film, which privileged narrative development. Manovich argues that database and narrative are “natural enemies,” and as culture becomes increasingly computerized, algorithms/data/computers are “competing for the same territory of human culture” — the right to make meaning out of the world. Although meaning, one could certainly argue, is the imaginative terrain of humans, not machines. I have yet to read Manovich closely enough to argue for or against his theory, but my initial interpretation is that database is a new form in the service of human narrative, rather than a form that stands in direct opposition to it.

Humans are narrative-driven creatures; we tell ourselves stories in order to live, etc etc… And even though algorithms seem to touch every aspect of our digital existence, we produce our own internal narratives (explanations) as to why, for instance, the TikTok algorithm is showing us what it’s showing us. We have a hard time letting go of narrative, even in situations where we are passive voyeurs of the aforementioned database (i.e. scrolling through TikTok). “Why should an arbitrary sequence of database records, constructed by the user, result in [narrative]?” Manovich wonders. Because, in our minds, even the arbitrary can feel preordained.

On the subject of novels, I finally read, and by that I mean very very closely read, the David Foster Wallace essay on television culture and postmodern fiction that everyone loves to reference piecemeal, to prove some general point about the state of our sardonic screen-obsessed culture. See: Catherine Shannon’s “Everyone is numbing out”; @yeetgenstein’s review of Bo Burnham’s “Inside”; and many many more references on Twitter and JSTOR. “E Pluribus Unum” is a sprawling, 40-page text in which Wallace tries to persuade us that “irony, poker-faced silence, and fear of ridicule are … entertaining and effective [but also] agents of great despair and status in US culture., and that for aspiring fiction writers they pose especially terrible problems.”

The best thing I’ve read in recent memory that referred to DFW’s essay is Olivia Kan-Sperling’s “Toward Pop Literature” in n+1, precisely because she frames DFW’s piece as about television’s impact on irony in postmodern literary fiction — not irony in our culture writ large, as others commonly have. DFW did not seriously anticipate a world where everyone, not just novelists, would be capable of distilling and producing their own narrative fantasies with ironic detachment (arguably, most users on TikTok engage with creators/other users on the platform in earnest), and while he spent a lot of time bemoaning the average American’s average daily screen time, Wallace had no good answer as to what the next novelistic form should be. Rather, he takes an unimaginative and unexpectedly conservative pivot in the essay’s conclusion: “The next real literary ‘rebels’ in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels, born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching … who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in US life with reverence and conviction.” New Sincerity.

But I think it’s less a matter of content and more a matter of form. What if the novel’s future is akin to a database? And for all our narrativizing impulses, will we be able to recognize it as such? I recently picked up Benjamin Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World, “a work of fiction based on real events” that weaves together loosely associated events, as one review put it… Might we think of each event, each chapter, as a uniquely significant “node” in Labatut’s novelistic database? From here, there is no returning to “plain old untrendy human troubles.” Every day, we are exposed to a multiplicity of perspectives and a multiplicity of possibilities. The challenge is to find a narrative through-line amidst the unintelligibility because, no matter what you call it, events, stories, narratives, data still demand to be closely read.