“It’s easy to typecast the mother.”

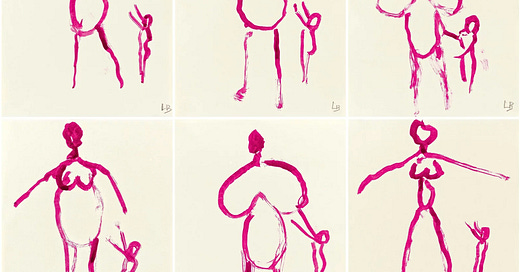

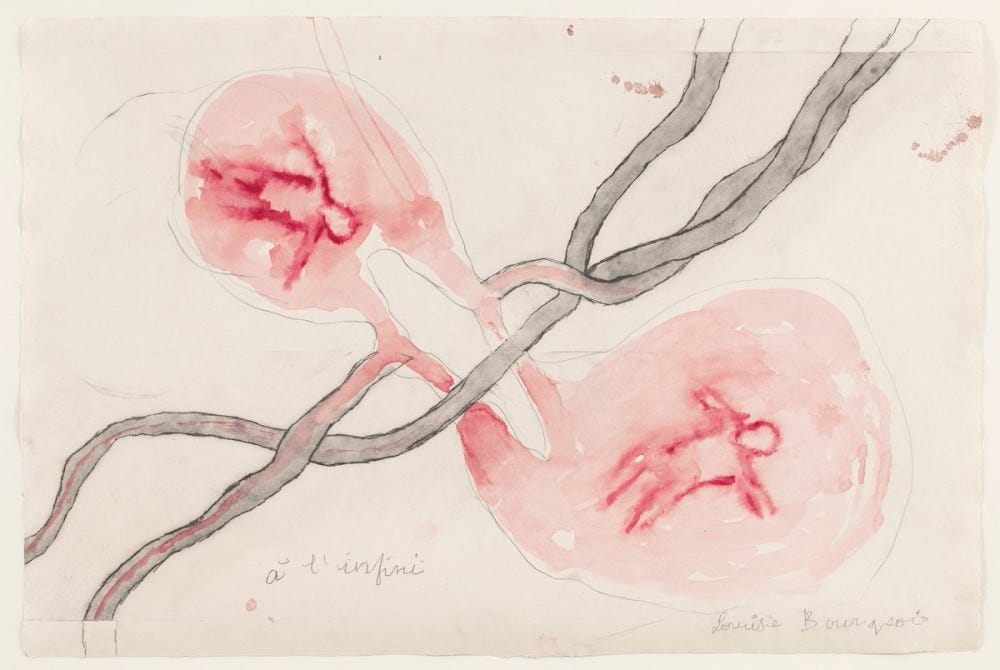

Fierce Attachments

Vivian Gornick, 1987

Minding the Gap

Bing Liu, 2018

Didi

Sean Wang, 2024

New Wave: A Documentary

Elizabeth Ai, 2024

My mother and I have a stalled relationship. She speaks to me the same way she did when I was a teenager, as if I need reminding to go about my daily life. Have I eaten today? Are my winter coats dry-cleaned? When was the last time I got my teeth cleaned? Am I eating enough?

Since we live on opposite coasts, it’s bearable to be spoken to like a fourteen-year-old every so often. We don’t have much to say to each other. Our calls rarely last longer than fifteen minutes. She likes to talk at me and I let her do the talking. For a long time, most of my energy was directed towards not hanging up. I participated in these incremental conversations, if one could even call them that, with daughterly obligation, incurious and even hostile to unearthing my mother’s inner life.

Recently, I tried asking her a question. She, ever evasive, did not offer a direct response. So I tried a different approach: listening. I began to notice certain temperaments and ticks in her speech—how she would skirt a comment I’d make and circle back to a topic that only she felt interested in discussing. I took note of the parables she’d repeat, the well-intentioned lessons she hoped to impart. It occurred to me that we’ve been having the same conversation my entire life.

What I find most compelling about Vivian Gornick’s Fierce Attachments, her 1987 memoir about her relationship with her mother, is Ma’s voice. Fierce Attachments gels together Gornick’s childhood with dialogue-driven vignettes of their present-day interactions. There are many memorable scenes, but this one I find particularly relatable. It takes place on a perfect autumn day. Gornick feels intellectually revitalized after spending an afternoon at the Whitney, and the first thing out of Ma’s mouth when they meet is, “Do you have rent this month?” It’s a universal experience had by daughters, their joy swiftly evaporating in the mother’s pungent presence.

“Ma, listen …” I say.

“That review you wrote for the Times,” she says. “It’s for sure they’ll pay you?”

“Ma, stop it. Let me tell you what I’ve been feeling,” I say.

“Why aren’t you wearing something warmer?” she cries. “It’s nearly winter.”

The space inside begins to shimmer. The walls collapse inward. I feel breathless. Swallow slowly, I say to myself, slowly. To my mother I say, “You do know how to say the right thing at the right time. It’s remarkable, this gift of yours. It quite takes my breath away.”

Their relationship is a marvelous, frustrating dance; each conversation almost always devolves into a hair-pulling power struggle. Gornick conjures her mother as a figure of unforgiving force and vitality—a woman “staring into the obscurity of all that lost life.” Ma foists her feelings onto her daughter because she is incapable of dwelling on this hollowness. Yet, we’re also privy to the great sadness behind Ma’s ferocity, and we sympathize with her childish allegiance to ideals like True Love, while spurning her insufferable itch for self-pity.

In any given story, it’s easy to typecast the mother. She is a supporting character, an antagonist or a flimsy foil for the central character’s growth. Such characterizations are lazy and ineffective. They fail to account for the surprising range of behaviors, emotions, and delusions that real people, real mothers exhibit and entertain. This is why I so routinely return to Fierce Attachments; Gornick nails Ma’s psychology without making her tediously explicable, a common tendency in contemporary media.

But [Ma] doesn’t get it. She doesn’t know I’m being ironic. Nor does she know she’s wiping me out. She doesn’t know I take her anxiety personally, feel annihilated by her depression. How can she know this? She doesn’t even know I’m there. Were I to tell her that it’s death to me, her not knowing I’m there, she would stare at me out of her eyes crowding up with puzzled desolation, this young girl of seventy-seven, and she would cry angrily, “You don’t understand! You have never understood!”

Call it the trauma plot or therapeutic realism or our collective eagerness to superficially analyze those we know and love. The writer Sam Kriss criticized this style of characterization as being “far too neat; [the plot] all makes far too much sense, this moment on which a person’s entire being is supposed to hang. When actual people act, there’s always an element of the inexplicable at play, the sourceless molten stuff we call human freedom. An abyss in the other, the dark hole of their subjectivity. But these people are wind-up toys.” Kriss had Netflix’s Beef in mind, but his frustrations are applicable to a wide range of media that’s been cheapened—or rendered predictable—by pop psychology. Should a character be constructed from the sum of their traumas?

“No one recovers from the sadomasochism of their childhood,” Adam Phillips writes in “The Magical Act of a Desperate Person,” an essay on tantrums.

Humiliation is the original sin passed between parent and child, Phillips posits, a power dynamic that carries consequences through the rest of our adult lives. It taints our interactions with others and, eventually, our own children. As much as we may hate our parents, we are destined to become them. The adult is a grown-up child, and the parent is “always in some sense … performing being a parent.” No one knows anything about living or child-rearing. We only pretend to.

This shared inheritance—or, as it’s in vogue to say, intergenerational trauma—gets at the tragic paradox of motherhood. Mothers may have their children’s best interests at heart, but they routinely fail to meet their true needs, a seeming result of not having their needs met by their own mothers.

Earlier this year, I saw three films that grapple with this filial tension to varying degrees of success. Success, by which I mean, an unflinching fidelity to the emotional truth of an event. (“People never tell the whole truth about themselves, and only ever tell part of the truth from behind the safety of a mask,” to quote the late Gary Indiana. “Why do you think fiction was invented in the first place?”) The films are quite different, but their shared commitment to excavating personal history, whether through documentary or fictional forms, link them together in my mind. They all attempt to atone for—or make sense of—their maker’s childhood wounds by contemplating the mother’s peripheral presence.

Sean Wang’s Didi (2024) follows the summer antics of Chris, a thirteen-year-old boy who’s taking out his adolescent angst on his mother, sister, and friends. Most of the film is shown through Chris’s eyes, but it also tries to fill in the blanks of his mother’s small life. Elizabeth Ai’s New Wave (2024) begins as a documentary-style exploration of a Vietnamese musical subculture that unfurls into a personal investigation into Ai’s family history. The filmmaker finds parallels between her estranged relationship with her mother and the fractured family dynamics common among Vietnamese New Wavers, who were desperate to find the joy and connection they felt on the dance floor. And finally, Bing Liu’s Minding the Gap (2018) dives into the turbulent upbringings of his skateboarder friends from Rockford, Illinois. The town is a hotbed for unemployment, drug abuse, and domestic violence, and skateboarding is how these young men cope and find community.

The films all attempt to atone for—or make sense of—their maker’s childhood wounds by contemplating the mother’s peripheral presence.

Minding the Gap, to me, reflects the apex of this genre, engaging the complexity of its characters without defaulting to the binaries of trope. Domestic violence is a fact of life in Rockford, and Liu dwells on the blurry line between victim and perpetrator—how violence can become a knee-jerk reaction to pain, leading victims of abuse to perpetuate its cycle.

Liu centers the documentary on two young men: Zack, who is white, and Keire, who is Black. They’d all skated together as teenagers but spoke little about their respective home lives. Liu spent five years (2012-2017) getting to know his subjects, shooting vlog-style snippets of them at home and work, tagging along to social gatherings and meeting their families. Zack and Keire are products of their environments, struggling to break from the enervating mold of life in Rockford. As the boys gradually open up to Liu, we, too, become so accustomed to Liu’s curious unobtrusiveness that, when he turns the camera on himself, the transition is jarring, even cold, as it plunges headfirst into the topic it’s been circling: Liu’s own experience with domestic violence.

Liu was routinely abused by his stepfather as a child, and his wounds, echoed through Zack and Keire, highlight an unspoken, albeit pervasive reality. There are few “talking head”-style interviews in the film, but Liu resorts to this impersonal format to speak to his mother Mengyue about why she condoned such abuse. Liu remains soft-spoken, even while he’s insistent. We can sense the hurt and frustration from behind the camera. It’s an uncomfortably direct approach: Mengyue’s expression is an agonized fusion of pain, desperation, guilt, and shame. Liu doesn’t delve into the details of his abuse (his stepbrother offers some brief, harrowing commentary about how his father behaved), nor does he share much else about his family, his mom’s romantic history, or their relationship. The condensed intensity of the scene—Liu’s mother has less than ten minutes of screen time—reverberates like a firework. Without further familial context, we see her not as Liu’s mother, but as an unknowable, anguished figure, a reserved woman bearing great regret and shame, who fails to find the right words to express all that’s contained inside her.

“I wish I can go over it and do again, do differently, but I really don't know what to say now,” Mengyue tells Liu, imploring her son to move on from the past. She, too, had been abused by Liu’s stepfather, and Mengyue copes by repressing these experiences. “Moving on” allows her to detach from these unspeakable horrors—silence as a method of self-preservation and protection.

The proper words seem to evade her (English is Mengyue’s second language) when confronted by Liu, and the remorse that surfaces feels simultaneously insufficient and overwhelming. The scene offers little explanation or resolution; we briefly dwell in the gravitas of what Liu’s mother reveals before the film cuts from Mengyue as quickly as it introduces her. We’re left wondering how the conversation amended or altered their relationship, if they’d spoken about this off-camera before. In withholding such information, the film allows for “the dark hole of [its characters’] subjectivity” to remain partly unfilled. It’s a resounding decision that reflects the ever-present uncertainty of human relationships and their underlying motivations. Perhaps the greatest truth Mengyue could admit was that she was at a loss for words.

Didi is a “coming of age” story, although the film isn’t necessarily about growing up. There’s a minor arc in Didi where Chris (Izaac Wang) shoots “homemade” skateboarding footage of his friends, which reminded me of Minding the Gap’s introductory sequence, where Liu films his friends skateboarding around town. The films are similar, but only superficially so—a homage to their hometowns that also touch upon the filmmakers’ relationship with their moms. However, Didi loiters in the in-betweenness of the summer between middle and high school, whereas Minding the Gap is about the listless transition to independent adulthood. And because Didi is not really about becoming an adult, it wholeheartedly basks in the false, feel-good sentimentality of childhood.

Wang’s depiction of early-aughts suburban culture, from stalking crushes on MySpace to sending emoji-laden messages on AIM, is a nostalgic ode to a simpler past—when your biggest problem is feeling excluded from your friend group or not having a ride home. Chris verbally spars with his sister and is mean to his mother Chunsing (Joan Chen), but these slights are forgiven in the end. Even when a situation feels dire to Chris, like when he gets cross-faded for the first time, its stakes are low, reflecting the relative safety of his and the film’s world. Didi is strongest when it’s a comedy in the endearingly awkward vein of Pen15. It’s when the film shifts into more dramatic territory that its characters, especially Chunsing, begin to feel thinly drawn.

Take the film’s climax, for example. Chunsing picks up Chris after he gets in a fight with a classmate. He lashes out at her in the car, and Chunsing moves as if to slap him, prompting Chris to take off running. He spends the night nodding off in an empty playground. In the morning, Chris returns home, finding Chunsing up waiting for him, and she tells him a story of his sister similarly running away. The scene is a tender moment, although not of mutual understanding between mother and son. It serves as an affirmation to reassure Chris and, by extension, the viewer that he is a good kid. The saccharine gesture is unsurprising, and undoes the script’s earlier attempts at imbuing Chunsing with some dimension. She is a skilled painter with creative ambitions beyond her housewifely duties. At the same time, Chunsing is stuck in Sacramento while Chris’s father is working in Taiwan and sending remittances back to the family. She’s briefly shown to be capable of anger and frustration, snapping at her elderly mother-in-law over some snide remarks. Yet Chen’s Chunsing is almost always soft-spoken and amenable, with a stern edge that is never quite steely, despite her life’s circumstances.

Didi would be a different film if Chris’s illusions about his mother were shattered, if Chunsing ended up slapping her son, if Chris had to face an emotional obstacle that required more than a half-hearted apology to resolve. It wouldn’t feel like “a warm hug,” as one reviewer described it, “by the end of an emotional rollercoaster.” Therapeutic realism that leaves the viewer warm and fuzzy. The best coming-of-age films—Lawrence Ah Mon’s Spacked Out and Justin Lin’s Better Luck Tomorrow are my favorite of the genre—take seriously the cruelty that teenagers endure and are capable of inflicting upon their peers and parents. (Minding the Gap does so as well.) The child’s world is no shelter, nor is it an entirely separate realm from the “adult” reality that pervades it.

Per Phillips, “There is something intrinsically and unavoidably humiliating about being a child. Every child has felt humiliated by his dependence on his parents—by his relative powerlessness in relation to the people he needs—and everyone has been left feeling vengeful by this ineluctable diminishment.” We see moments of that powerlessness in Didi, where Chris acts out, but the script is overwhelmingly focused on affirming his world-view, in lieu of disassembling it.

Chris is privy to brief flashes of disorientation when he’s belittled by his friends or spurned by his sister. Still, Didi maintains a clear distinction between the child’s world and the adult’s, ultimately reinforcing a childish worldview: The mother as a virtuous figure of authority, who selflessly cares for her children, always capable of finding the right words to assuage their worries, no matter their wrongs.

Towards the end of Elizabeth Ai’s New Wave, the filmmaker asks her once-estranged mother if she’s ever considered going to therapy. “Therapy,” her mother responds, incredulously. “Why?” I went to a screening of the documentary with my dad, who’s about a decade younger than Ai’s mother. Still, I consider them to be of the same generation—refugees who fled Vietnam as adults (although my dad was barely one at 20).

The row ahead of us burst into giggles at the on-screen exchange, presumably from having had similar conversations with their parents. I didn’t find the interaction funny; it actually made me sad. The incongruity of the mother’s response highlighted the insurmountable chasm that feels inherent to most mother-daughter relationships. Language, in such instances, fails and unravels. As humans, we naturally crave understanding on our own terms—understanding as its own private language. (Recall how Gornick imagines her mother crying out: “You don’t understand! You have never understood!”) Therapy, for mine and Ai’s generation, has been the go-to system for decoding these differences, despite it being a faulty blueprint for mutual understanding, self-reflection, reconciliation. We can’t always account for the muck of our motivations or the ripple effects of our parents’ old wounds.

The Vietnamese New Wave emerged in the ‘80s and ‘90s, its shimmery, synthy tunes inspired by popular Eurodisco tracks of an earlier era. The musical craze was an emotional outlet for teenage refugees struggling to acculturate into American life. “The music sounds innocent, but the scene was not,” said Ian Nguyễn, a New Wave DJ. Ai’s own interest in New Wave was sparked by her aunt Myra, who served as a maternal stand-in for her absent mother. Songs like “Jump in My Car” and “Boys in Black Cars” were the musical backdrop to Ai’s childhood as a freewheeling tagalong to her aunt and boyfriend. Ai was too young to be socially involved in the scene, and the documentary’s first half excavates its history through interviews with figures like Nguyễn and Lynda Trang Đài, a Vietnamese American pop idol.

A common thread unites Nguyễn’s and Trang Đài’s story: Music presented an escape from the tumult of their lives. The nightlife scene’s punk-ish roots helped them create a distinct identity, separate from the homeland nostalgia that weighed down their parents and mainstream American culture. The documentary alludes to the war’s psychic effects on this rebel subculture, but its latter half is more concerned with reconciliation between Ai and her mother than the emotional casualties weathered by the community.

Specifically, I was struck by a story Nguyễn told about his time as an itinerant DJ, sleeping in cheap motels with a dozen other New Wave friends. One night, a friend brandished a gun, loaded it, and pointed it at Nguyễn’s friend. He tried to shoot it but it didn’t go off. He then pointed it at Nguyễn. The gun stayed jammed. Finally, his friend put the gun in his mouth. The documentary interrupts Nguyễn’s narration, drawing it to a swift close with the sound of a gunshot. Instead of lingering on Nguyễn, the film shifts to a visual dramatization of events, underscored by upbeat music.

On my second watch of New Wave, I was so jarred by that cut, and upset at how the film only grazed the surface of such a horrifying event to maintain a mood of contrived joy. I don’t take issue with the documentary choosing to withhold more details of the tragedy from us. But its execution felt shallow. The scene failed to adequately reckon with the pain of such an event, hastening past its psychological epicenter to tie up the loose ends of Nguyễn’s story. How did this incident psychically impact Nguyễn? Were there other instances of violence or suicide in the scene? Nguyễn describes his retreat from DJ’ing shortly after his friend’s death, and concludes on a rushed note of resolution: Nguyễn discusses how he repaired his relationship with his father, who was once adamantly against his interest in New Wave, shortly before he passed.

“In absence, assumptions become our truth,” Ai says of her newfound relationship with her mother. The two had failed to reunite for over a decade; for years, they were locked in a long-distance power struggle fueled by resentment and shame. When Ai finally came to visit her mother, they spent three whole days talking. Most of this occurred off-camera, although snippets are shown in New Wave’s conclusion. The documentary appeals towards open communication as a conduit for healing, reveling in the potential of rekindled connections.

It’s worth noting that conversation is the raw material of both documentary storytelling and psychotherapy. In his book On Getting Better, Phillips cites the French philosopher Michel Henry: “‘The truth of history is the truth of language,’ Henry wrote, as if to say: the only truth we have is in language, and we need to acknowledge that, and all that it precludes (especially in psychoanalysis).”

As a medium of exchange, conversation isn’t therapeutic. Nor is it easy. Good conversation can facilitate intense intimacy, even though what’s shared is always at risk of suddenly faltering: The other party might retreat into defiance, or a person’s fickle moods might preclude them from listening in earnest. With my mother (as Gornick is with hers), both parties bring a different set of terms to the table. Conversation becomes an ongoing negotiation that, in rare moments, can carve out a haven of understanding between two people. But that haven is temporary; it never lasts for long. There are also instances when we’re at a loss for language, or when the loss of language is symptomatic of something uncomfortable, even excruciating, of pain that’s repressed, denied, or forgotten. Better to not say anything at all than to admit something we’d regret, fear, or despise. That’s what frustrates me about stories that insist upon understanding or empathy as an off-ramp to resolution, as if its direction all hinged upon one crucial moment. What strikes me as more true to life is our persistent and minor failures—our inability to empathize, to say the right thing, to show up for our loved ones when they need it. Fierce Attachments concludes mid-argument, with Ma urging Gornick to walk out of her life, and Gornick bravely pauses their story there with her “half in, half out,” contemplating stepping out onto the street, showing Ma that it’s over. It’s in this prolonged second of deliberation that a person is forced to question their identity and values, their strengths and weaknesses. A discerning writer or director knows how to dramatize that, but the decision itself is not so rare. We fuck up, we forgive, we fight and fuck up again. With our partners, our mothers, our neighbors, our friends. With my mother, I am always searching for the right way to say something. This leads me, more often than not, to say nothing at all. I’m always half in, half out.

Reading:

’s Halloween-themed story, “Humiliation,” in Hobart; Gary Indiana’s essay “Five O’Clock Somewhere”Listening: A Vietnamese cover of Brother Louie by Modern Talking

Eating: Tibetan beef dumplings (Sha Momo) at Cafe Himalaya

Enjoyed reading this. Coincidentally, I'm thinking of writing something about the horrors of motherhood as depicted in certain novels and movies.

Really enjoyed this read and how you highlighted the role of conversation in documentaries. I didn't expect New Wave to resonate with me so much, but it really held a mirror to my own difficult conversations with my mother. Definitely an important watch for all Vietnamese Americans.