Cyborg nostalgia

How did AI—science fiction’s infamous dystopian boogeyman—become cringe?

Last summer, the Criterion Channel released a timely line-up of films about artificial intelligence. Around that time, as I recall, there was a lot of paranoia about the future of art and AI—paranoia that has, for better and for worse, subsided as tech companies raced to incorporate AI into their existing suite of products, normalizing its novelty among users who previously found it suspect. With Apple’s latest AI announcement, I’ve been thinking about how we’ve become inured to, or even bored by, the concept of AI, even as its rapid developments raise concerns about digital privacy, surveillance, and intellectual property. How did AI—science fiction’s infamous dystopian boogeyman—become cringe?

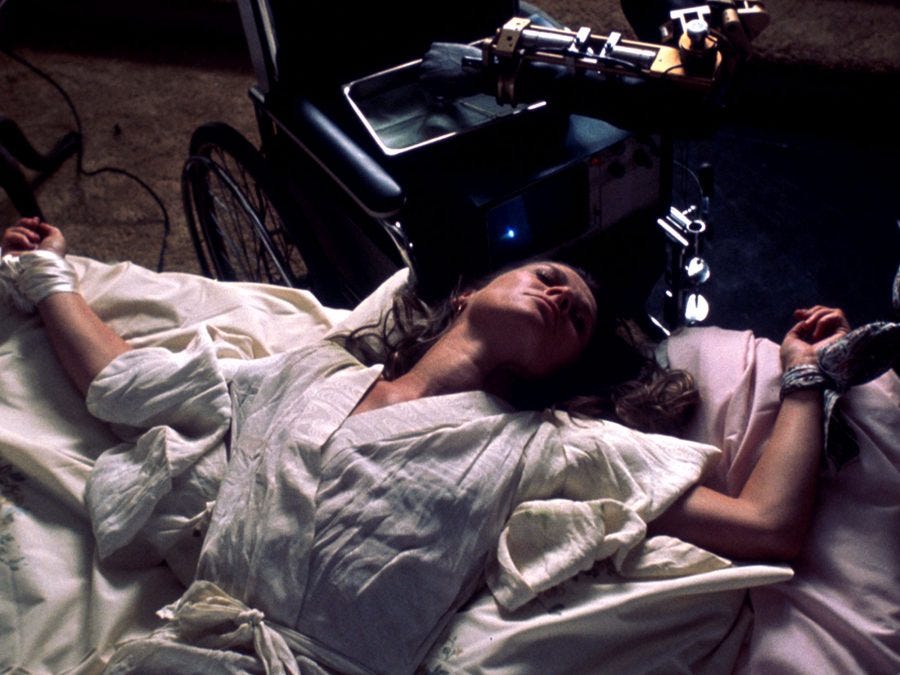

The earliest films in the Criterion Collection are from the 1970s and surprisingly goofy. The one exception is Demon Seed (1977), a bizarre, Cronenberg-lite movie about a woman who is taken hostage in her own home by Proteus, an AI computer program developed by her husband. Proteus plans to impregnate the woman to bear a child so that it can achieve a “complete” form—its intelligence “alive in human flesh,” capable of touching the world.

The film’s premise loosely reminded me of Titane (2021), Julia Ducournau’s body-horror flick about an on-the-run serial killer who has sex with cars. I like Titane for its boldness—how Ducournau infuses touching moments of hope into the protagonist’s deprived world, culminating with the birth of her mutant child. On the contrary, Demon Seed ends on a note of haunting resignation, as its characters bask in the inevitability of catastrophe. Humans are quick to dismiss a computer, Proteus says, but less so another human. Its cyborg child, which seems to be a fleshly vessel for Proteus itself, won’t be so easily ignored.

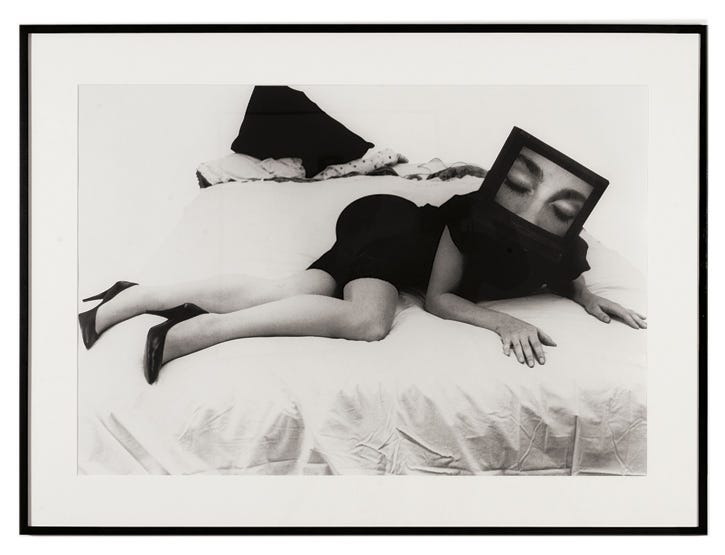

I love watching older movies about cyborgs and AI even if, as Demon Seed proves, they aren’t very good. There’s an icky, tactile pleasure to seeing how a film like David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983) tries to anthropomorphize a machine, rejecting the slick, immersive smoothness so characteristic of modern devices for the abject, “the new flesh.”

This smoothness, I’ve noticed, permeates throughout contemporary films about AI, like Her (2013) and After Yang (2021). Blade Runner 2046 (2017) is a rare exception to this Apple minimalism, a polished aesthetic that feels imaginatively stunted, even “radically unsexy,” as Stella Bugbee writes of the fashion in Her: “The clothing feels stunted by a culture that has stopped thinking about fashion. When you live so much in your own imagination, communicating through screens and ear pieces, who needs innovative clothes?”

The same could be said about the cybernetic body in contemporary AI films—once an uncanny territory rife for exploration and exploitation. The cyborg is a hybrid species, a “condensed image,” a post-human subject born from the dregs of rapid industrialization. Older films exemplify this paranoia of a parasitic technology invading and infesting people’s bodies and bloodstream, a fear that feels quite old-fashioned, as our relationship to computers has veered towards symbiosis: I think of my phone as a prosthesis—a second brain, a second eye—that is so seamlessly “integrated” into my life that I no longer think of it as a separate, unruly entity, but a portal to my most primal selves.

The cyborgs in these newer films, if they take forms outside of cyberspace, are deceptively human-looking—a sign, I suppose, of the futurism in After Yang and Blade Runner 2046. Cyborgs either “pass” as humans or their existence is siloed within an unremarkably small, transportable device. While programmed to be “intelligent,” their world-view is seemingly limited to what their owners show them. The “sentience” of an AI like Her’s Samantha or Blade Runner’s Joi appears to be wholly disentangled from the complex cybernetic web that powers her, as her “humanity” is emphasized over her non-human capabilities.

While these films explore relevant questions about technology and humanity, there is little sense of the imaginative “other-ness” that is palpable in vintage AI and cyborg flicks like Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989), which features a Japanese salaryman grotesquely transforming into a metal cyborg (complete with a drill dick), or Teknolust (2002), where a bio-geneticist named Rosetta Stone (Tilda Swinton) utilizes her DNA to breed three live self-replicating AI cyborgs. While watching Teknolust earlier this week, it occurred to me that perhaps the evolving visual representation of cyborgs and AI (in Hollywood, at least) reflects the gradual dismantling of the computer’s physicality.

Major developments in consumer hardware have stalled since the advent of the iPhone. The paper-thin screen is everywhere, its design and interface characterized by this prevailing smoothness. New devices have fewer and fewer ports, and with wireless charging and bluetooth headsets, there is diminishing use for cords and cables. User preference has shifted towards smaller solid-state drives (SSDs) rather than hard disc drives (HDDs)—the black box that I grew up calling the computer’s “heart.” I thought the screen was its “brain,” although I’ve long lost the logic of the analogy.

We’ve succumbed to the unyielding tide of software that is eating the world, abandoning our unwieldy attachments to hardware. The boundary between the physical and the virtual are more porous than ever, and software masks the extent of this cybernetic world and reinforces this sense of hyperreality.

The characters in Her and After Yang exist in a world much like our own: AI is a commonplace technology that warrants little surprise or skepticism. Even the set designs feel oddly sanitized, as if imported from a nearby Apple store. These movies revel in the emotional core of human-machine relationships, positioning the alien as something like us—a human without a body who is capable of feeling. This shift from horror and fear to relational empathy is compelling, and imbues these films with pathos, evoking a melodramatic depth that is often lost in the older, campier works about AI.

Yet, I wonder what we lose when we “humanize” the cyborg from its cyberpunk roots, remaking its body after our own image, or into a body-less voice. I long for the unruly physicality of the tentacular computer in Tetsuo or the video-game whimsy of Teknolust—movies that are arguably about love as much as they are about the fear of the unknown. Perhaps the boredom we feel towards AI is more towards the narrow applications promoted by the tech giants: AI as productivity tool, as a skills substitute for creative workers. What can we learn from these arguably dated visions of the future? And how can we, as the filmmaker Asuka Lin writes, develop “an evolved language for the masses, speaking of the marginalized body and psyche in relation to this modern age of techno-hegemony”?

Some forthcoming/recent work + news:

I spent April & May recapping HBO’s The Sympathizer for Vulture. This was my first attempt to doing an episode-by-episode “review” of a television show, and it presented many interesting challenges! Namely, it reminded me that I am a slow writer who needs time for my ideas to simmer. I’m not proud of every installment, but it was a fun exercise.

I have a short review of Yasmin Zaher’s The Coin in the next issue of The Believer.

I wrote about Catalina Ouyang’s exhibit Trick at Lyles and King, which closes on June 15. If you’re in New York, I encourage you to go see it!

I have a forthcoming essay on the Vietnamese musical variety show Paris by Night in Still Alive Magazine’s third issue. I have a lot of fun reading stuff on their site, and I’m excited to chat more about PBN when the piece publishes.

Finally, may we all embrace LEISURE this summer!!!

There's a short film from 2014 I keep going back to re: AI - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YrXWWXGKowo& Henry Dunham's first movie, I keep coming back to how quickly a true AI would use the universe of data to manipulate humans. So far removed from GrokAI saying Elon isn't "woke" or whatever.

Interesting post and this idea of something that's actually highly relevent (e.g. AI surveillance risk) becoming a passe topic of discussion folds into a broader question about how memes (of any kind) are traded in the marketplace of ideas.

I'm increasingly of the mind that memes (e.g. "xyz is a risk we should worry about") in the political class are constantly being used as signaling tokens, i.e., they're "bought" or "traded" as a means of declaring a particular political affiliation or to signal class differentiation.

The content or truthfulness of a meme, in many cases, is secondary.

See how this has played out with discussions around AGI risk specifically, as increasingly cynical actors enter the space of discussion.