Curator of Secrets

A live Substack reading, Challengers review, Hana Vu's Romanticism

I tend to go long here, but I’m keeping this one short.

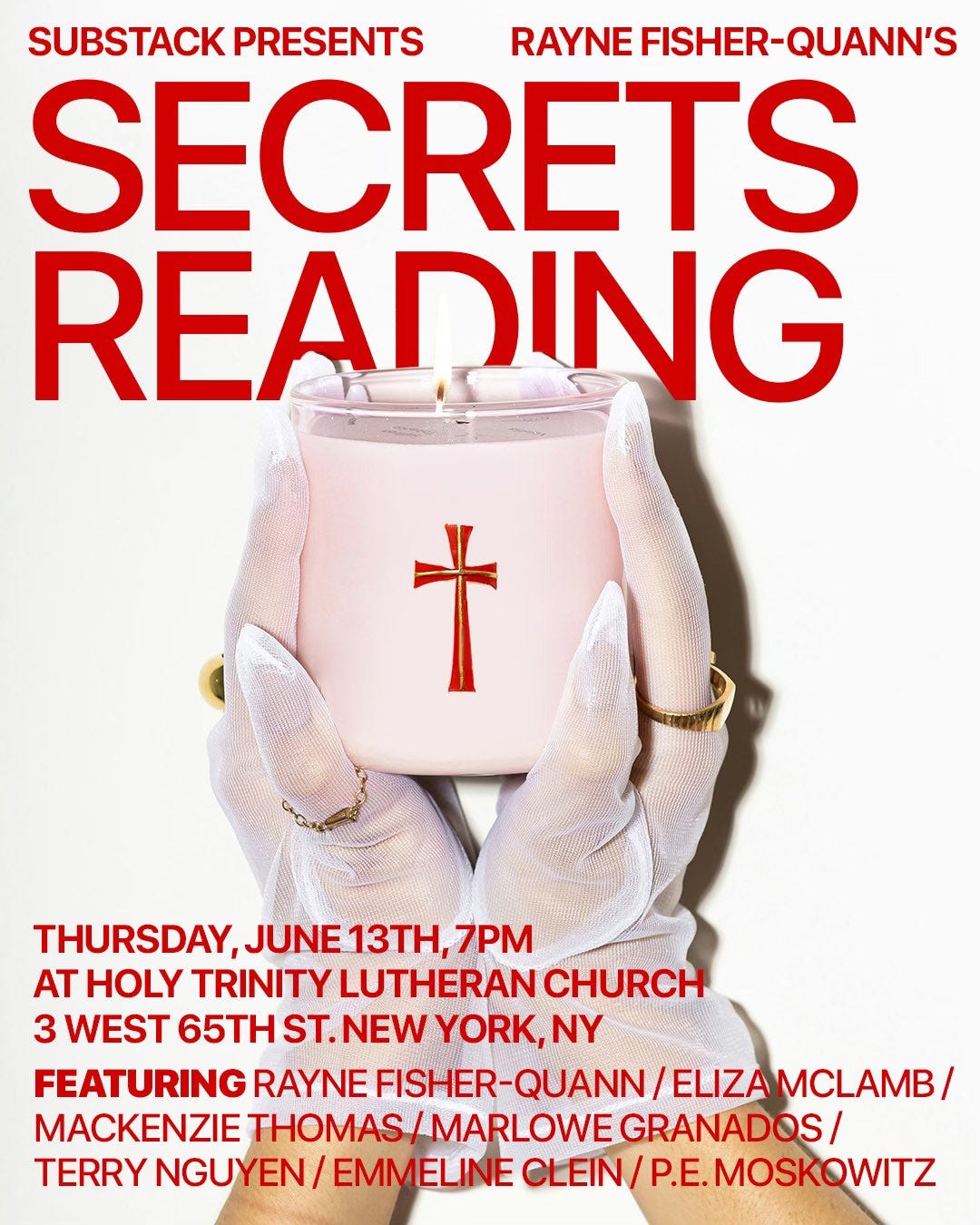

On June 13, I’m participating in a live Substack reading hosted by

Rayne Fisher-Quann, ft. Eliza McLamb, P.E. Moskowitz, Emmeline Clein, Mackenzie Thomas, and Marlowe Granados. Everyone is writing about a SECRET (!) they’ve never shared before, and the pieces will be ANONYMIZED (!!) and switched between readers. It will take place at a church on the Upper West Side — the one famously crushed by the Marshmallow Man in the original Ghostbusters. RSVPs will open at noon ET tomorrow, and I’ll pop the link in my Substack Chat upon release!“I have never tried to be a music critic but I’m a critic about everything else.”

I’ve had Hana Vu’s Romanticism on repeat since No Bells’ Mano Sundaresan got me early access to the singer-songwriter’s sophomore record in March. I’ve never felt equipped to write music criticism, even though I realize that it’s just like any other type of criticism. I wasn’t about to start with Romanticism. While abroad, I wrote some short fiction based on the album’s tracks and visual concept — inspired, partly, by how Vu wrote her 2019 EP, Nicole Kidman/Anne Hathaway, after watching The Hollywood Reporter’s actress roundtable interviews; her lyrics imagine backstories for these women. You can read all twelve shorts on No Bells. Below, I’ve quoted some of my favorite shorts and sentiments:

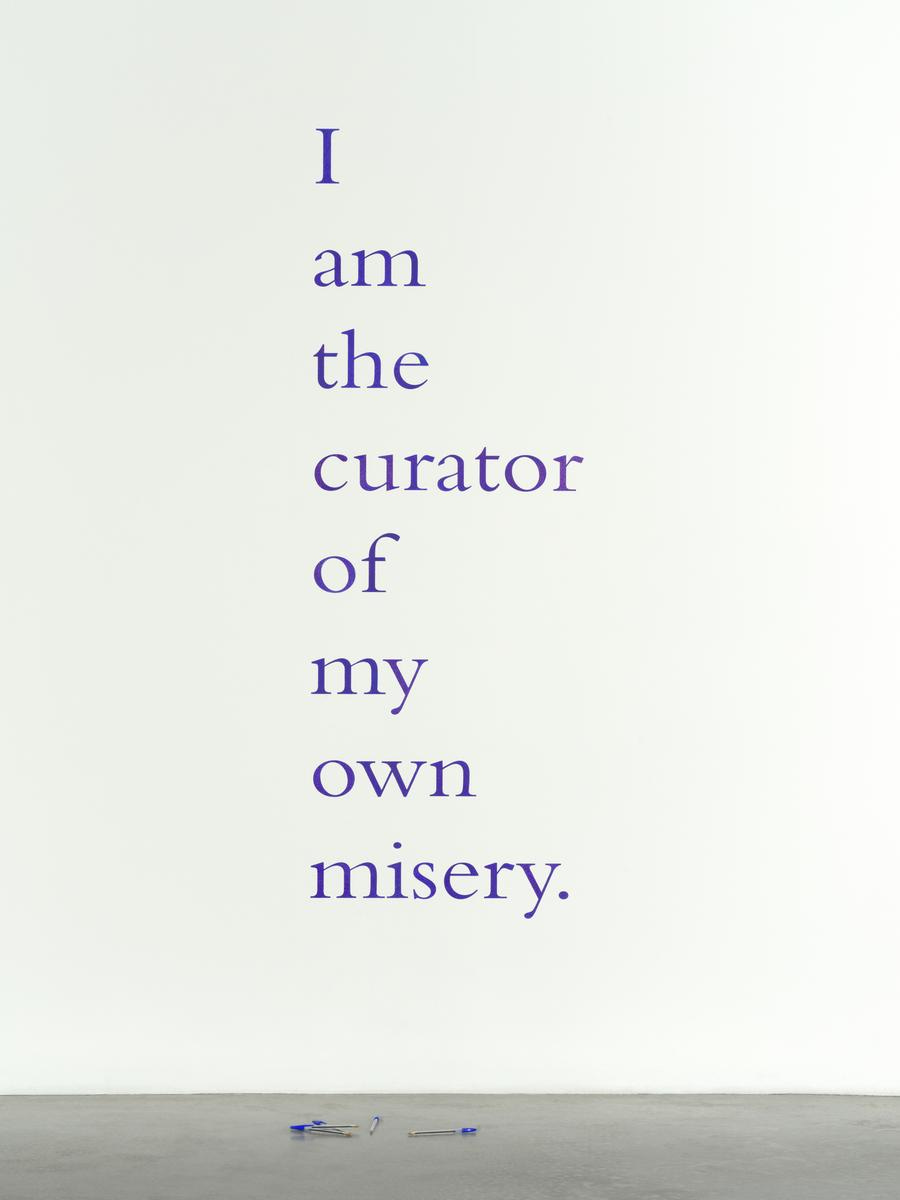

HOW IT GOES: My stockings are inside out. I can’t get them outside in. When I flip them, they stay inside out. I wear my inside-out tights to the museum, and the words, “I AM THE CURATOR OF MY OWN MISERY,” slap me across the cheek. I am tired of being assaulted by words, I confess to no one in particular. In the next room, I take out my phone to photograph the words, “I AM NOT EXOTIC. I AM EXHAUSTED.”

HAMMER: I wandered around Madrid, lonely as a cloud, until I found a group of Chinese tourists. With them, I was no longer a liability, just another Asian face in a crowd of visors and selfie sticks. We went into the Prado. The Spaniards have a strict no-camera policy so we were scolded in every room. I do not know why I invoked the we when I was alone then, uncertain and unassured of my station in life.

22: It was liberating, at that age, to be seen and not heard. The summer was a shapeless encounter and I was a vagrant phantasm, translucent in my mesh, methods, and mannerisms. Everyone I met was inclined to think of me as all surface and no depth, a pretty face to smile for their projections. At the time, I was content, flattered even, by these boorish instincts, by how simple it was to persuade people of my complicity in the current state of affairs. I met artists, bankers, influencers, and bouncers. I left rooms unexcused, dizzy and half-drunk. Most days, I went to the movies and sat alone in the loud dark, contemplating the sweet aftertaste of youth in my vanishing hangover.

CARE: Like you said, Who could claim to know anyone in this economy? True knowledge was a tease. We’re only afforded glimpses of another’s personhood so significance is relegated to objects, locations, text messages, songs. I can’t help that my generation interprets care as a gesture: a virtual heart, cab money, “if he wanted to he would.” From beyond the fog of limerence, I realized that you were like most men I’ve despised: self-pitying bastards who think of themselves as the sad clown, always laughing on the outside and crying on the inside. You can’t fool me.

Challengers sidelines the risks and complications of sexuality for a sensual camaraderie

In Challengers, everything is about tennis except tennis. Tennis is about desire, something that is different, although not entirely divorced, from sex.

I watched Challengers on opening night with

’s Akosua Adasi. In the words of Gwyneth Paltrow: I laughed. I cried. I sweated. I danced. I had a shot. I… had many epiphanies. I liked it so much I considered watching it again in Madrid, but I didn’t want to be distracted by the Spanish subtitles. In London, I had a spirited conversation-slash-debate with my friend Sanam, who was less impressed by the film, which ultimately helped inform my critical perspective on Challengers. I saw it again a few weeks later, and left the theaters a little less enthralled. But when I read about why critics found the films so lacking, I found myself disagreeing with their qualms. You can subscribe to Flaming Hydra to read my essay in full.Sex need not be a precondition for sexiness, but some critics have taken issue with Challengers’ erotic posture, or lack thereof. The film “teases at a complicated sexuality that the story desperately reaches for but never grasps,” writes Vulture’s Angelica Jade Bastién on the homoerotic chemistry between Patrick and Art. “What benumbs Challengers isn’t a lack of sex … but a lack of talk about sex,” according to The New Yorker’s Richard Brody. P.E. Moscowitz of the newsletter Mental Hellth claims, “The movie is very sexless. Not only in the sense that no sex happens in it, despite it ostensibly being about sex, but in its overall mood and tone.” The general gist of these arguments is that Challengers leverages sexuality in lieu of sufficient characterization.

I don’t entirely disagree. But I think such expectations — that sexuality must be bolstered by “complexity” over the arbitrary allure of attraction — reflect the sexlessness of the current cinematic landscape, such that the definition of pornography is even up for dispute. Challengers is not a chaste movie, nor is it passionately carnal. Its eroticism is displaced by tennis, tennis being a proxy not only for sport and physicality, but for feeling, for a game in which the characters subsume their fleshly desires for the pursuit of athletic domination. (The couple’s dynamic in Phantom Thread (2019), a movie that derives and displaces its eroticism in dressmaking, makes an apt comparison.) Much like foreplay, this sublimated sensuality can be erotic or frustrating; it all depends on your personal preference.

What’s also interesting is how people have hyped up Challengers as an erotic thriller when, to me, it is so clearly a sports movie, down to its ping-pong-style structure. The film infuses familiar character types, like the underdog (present-day Patrick; younger Art), the femme fatale (Tashi), the insecure star athlete (Art), with new quirks and hints of an errant sexuality. The script also employs familiar plot points — the star athlete suffers a career-ruining injury (Tashi), the underdog develops into a star (Art), the husband (Art) is cheated on with a college ex (Patrick) — that on the surface might seem predictable. But like any domineering lover, Challengers gets off on withholding. The narrative strategy sustains tension throughout by offering glimpses of past events as the final match unfolds: It teases the viewer’s curiosity by stripping down the stakes of the trio’s game, layer by layer, as the film builds towards its in-game climax.

In Challengers, everything is about tennis except tennis. Tennis is about desire, something that is different, although not entirely divorced, from sex. “You think that tennis is about expressing yourself, doing your thing,” teenage Tashi tells Patrick. “You don’t know what tennis is.” Tennis — when played at the highest and truest level — is like a relationship, she says. A raw, reciprocal force that emerges on the court between two (or more) players, a purely physical language understood by everyone watching. The same could be said of the trio’s relationship. Individual self-expression is limited for the sake of the game.

Of her US Open match, Tashi says, “For about 15 seconds there, we understood each other completely. So did everyone watching. It was like we were in love. Or like we didn’t exist. We went somewhere really beautiful.” Tashi craves this sublime reciprocity, more than love and sex, more than Art or Patrick. There is an impossible purity to her idea of tennis. This vision of the game is both wholesome and impossible, a “true love” beyond reach since her injury.

Challengers coalesces around Tashi’s desire to witness real tennis, and she is integral to the plot’s competitive melodrama. But Tashi is no femme fatale: Her sexuality endangers no one. The reasons for her infidelity are quite mundane, as are Challengers’ sexual stakes. While compelling to watch, this makes for a curiously abstinent, though not entirely unsexy, plot. Sexual fulfillment is secondary to sport when the closest thing to an orgasm is Tashi’s guttural “COME ONNNNN!” on match point. Even in its transgressions, there is a wholesomeness to Challengers’ camaraderie that has garnered it popular success and unpolarized enthusiasm. It’s too reductive to call Challengers a live-action sports anime, but it’s this wholehearted devotion to the game that cements its feel-good conclusion — and spawned an onslaught of fanfiction. Who actually wins? What happens to Art and Tashi’s marriage? Will Patrick quit tennis? This is no matter to Guadagnino, who claims that the trio goes back to the hotel together after the match — the subtext being that they finally hook up. But like most of the sex in Challengers, it’s left to our imagination.

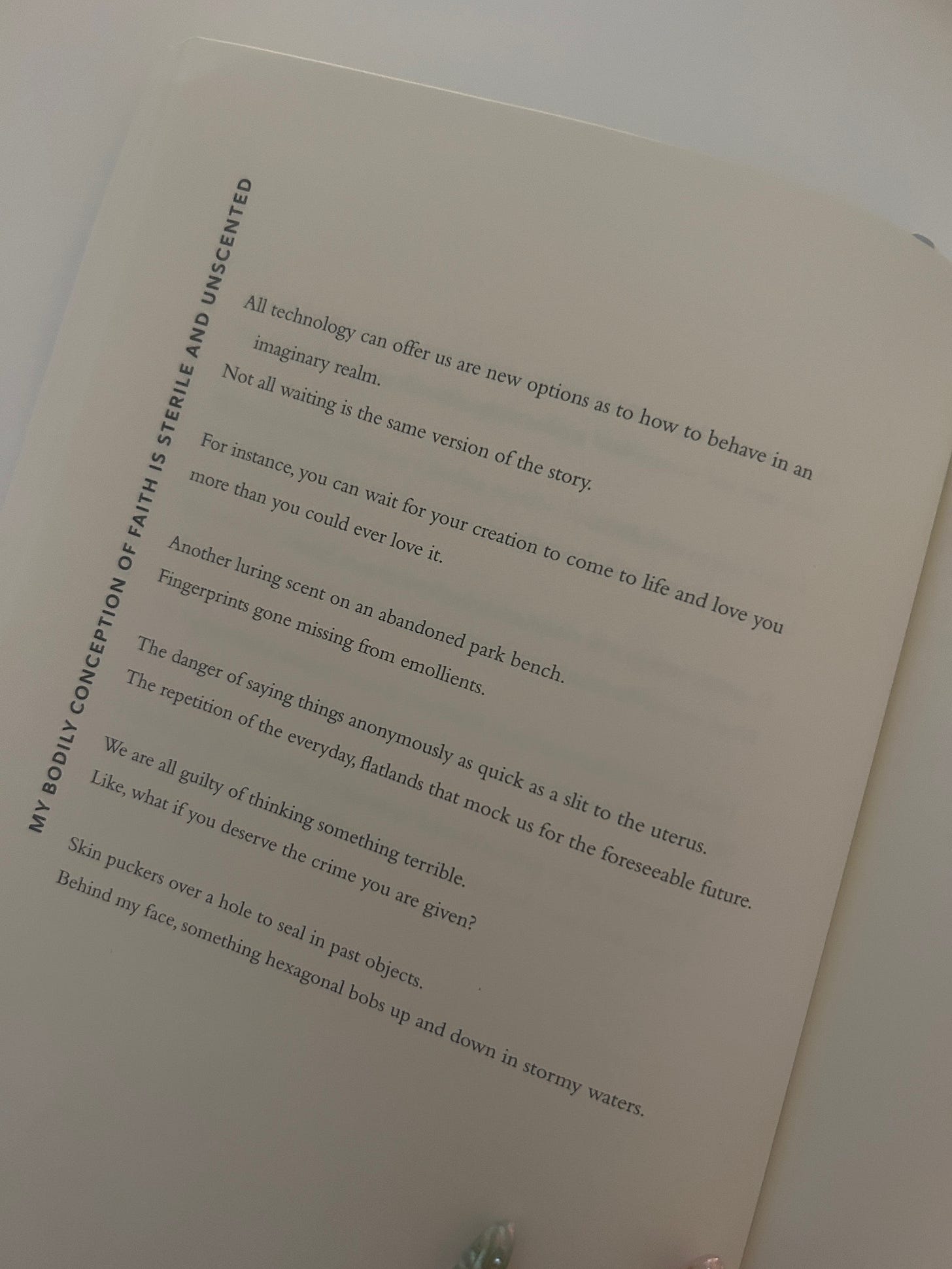

Community Garden for Lonely Girls

My friend Christine Shan Shan Hou, a poet and artist, recently sent me her 2017 book Community Garden for Lonely Girls. It’s a funny, chatty (to use Hou’s description) collection that is wonderfully surreal and sensual.