THERE IS A LINE from Elizabeth Bishop’s Art of Poetry interview that often makes the rounds on Instagram: “There’s nothing more embarrassing than being a poet, really.” I’m guilty of sharing it, although lit-posting is undoubtedly more embarrassing than the private endeavor of writing poetry. Shame works in mysterious ways. It is also a valuable barometer for what you can or cannot bear about yourself. Most days, when the writing is going (and lately, it has been going), it feels like the poem is working on me—not the other way around. The best metaphor I have for it is bodywork, like a Thai massage that hurts like hell but feels great afterwards. Louise Gluck describes writing poetry as “a condition of ecstatic detachment.” When a poem is complete, “no record exists of the poet’s agency. And the poet, from that point, isn’t a poet anymore, simply someone who wishes to be one.”

In this state, I am torturously focused, fully engaged with language. Less so on narrative and meaning. I dwell on structure, syntax, punctuation. How best to begin or end a line? How might the poem appear in its final form? Gluck, again: “To perceive [the poem] at all is to be haunted by it; some sound, some tone, becomes a torment—the poem embodying that sound seems to exist somewhere already finished.” When I am working towards this vague ideal, I am most doubtful of my ability to think straight, as if thinking straight comes naturally to writers. The mind reveals itself as a disorganized blob of images and ideas, and I am paralyzed by the prospect of sifting through the trash for promising nougats.

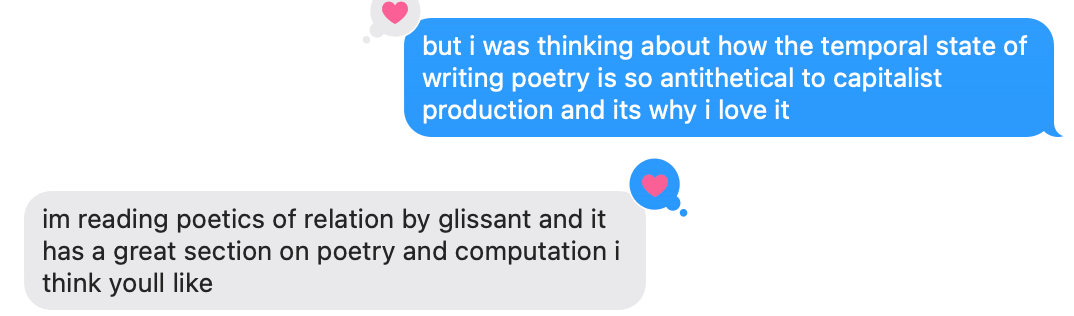

After years of writing for public consumption, with journalistic clarity as my guiding ethos, I’m much happier approaching the page as a space for play. It feels like an anachronistic privilege to be devoting myself to poetry when every industry, from public education to advertising, is selling its soiled souls to the automated pursuit of productivity for maximum profit. People are oddly eager about the time they’re saving by not writing, thanks to ChatGPT. I understand not wanting to draft a work email, but I wonder if we’re beginning to lose something crucial once this optimization mindset extends to personal correspondence and even journaling. Sontag: “In the journal I do not express myself more openly than I could do to any person; I create myself.” How terrible it must be to lose the desire to create yourself!

Three years ago, I published a two-part essay on how writers might benefit from considering ChatGPT a tool rather than a threat. I’ve also argued for more specificity in how the publishing industry considers and categorizes machine-assisted works that have artistic merit. I don’t wish to retract or necessarily amend what I’ve written in that department. I’ve just grown wary of the consequences of AI’s relative ubiquity—how no one, no matter how much they resist, can operate outside of its programmatic infrastructure. AI was designed to be all-encompassing. My review of Hito Steyerl’s Medium Hot delves into the ethical dilemma faced by visual artists, whose work is increasingly caught in the blur between representation and extraction. Steyerl outlines how our visual culture is shifting towards machine-generated abstractions. Soon, most images circulating on the internet will no longer be photographic representations of reality, but data-based renderings that are essentially programmatic fantasies.

As a writer, I’m less interested in the question of plagiarism or whether the reading public can tell the difference between what’s written by a human or a machine. I’m interested in what happens to our minds when people are systematically discouraged from thinking, from putting pen to paper. There is something particularly dire at stake if you believe, as I do, that language is fundamental to the human condition. That it is a conduit to our innermost desires, beliefs, and sense of self(s). Human perception of the world is uniquely dependent on language, even if, at times, certain words might escape the mind or certain circumstances might render one speechless. Yet it has become alarmingly easy to neglect language’s role in shaping one’s inner and outer worlds when ideas can simply be prompted into existence. Why think of a response to anything, whether on a dating app or in a classroom, when AI can simulate originality and thoughtfulness on your behalf?

ELIZABETH HARDWICK ONCE SAID that “style [on the page] is more than personality; it’s your character.” A good writer isn’t always a good or interesting person, but there is merit to the idea that style is a shorthand for the illusion of one’s character. As writing becomes a diminished practice, trade, and craft, how might the widespread deployment of AI flatten our means of social self-expression? The feelings will remain, stranded in our bodies. What’s gradually diminished are the older forms of expression, like letter-writing, which is not so much a “lost art” as it is a temporally impractical one. The contents of a letter and an email could be one and the same. The difference lies in their speed—how the newer technology collapses the distance between writer and receiver, inevitably influencing the contents of the letter-turned-email and, later, the email-turned-text.

And while a message can be sent instantly via text and email, there is some stall time during its composition, when the writer reflects on what they want to convey. AI threatens to eliminate this process entirely; its “innovation” is the instantaneous production of thought. This rapid meaning-production scheme is extremely practical for workplace communication, but renders interpersonal correspondence astonishingly impersonal, by virtue of its immediacy: Last winter, my friend R received an Apple AI summary of a break-up text before she had the chance to read the 500-word text herself. Apple AI’s attempt to reduce the friction of communication between R and her boyfriend only further alienated them both, as the “original” meaning of the message was overwritten by AI’s interpretation of it. That, in turn, affected R’s own response.

With AI, immediacy extends to how we think, not just in how we communicate. In Immediacy: Or the Style of Too Late Capitalism, Anna Kornbluh defines it as “a hurry-hurry that compresses time into a tingling present … immediacy encloses while delivering everything close: the world at your fingertips … the flexible psychology surfing these urgencies and proximities is self-possessed and transparent.” Constant connection, unfettered self-possession. ChatGPT streamlines the making of an “I” that can be readily understood, eager to close the ever-present gap between writer and reader. It speeds up the discursive process while simultaneously diluting voice. Ask the machine to revise something, and it will default to linguistic conventions, erasing quirks to distill what it considers meaningful in any given paragraph or piece of writing. More often than not, it seeks to summarize meaning, in lieu of formulating new meaning or epiphanies. The result is an inoffensive programmatic vernacular, akin to therapy speak, that is weaseling its way into popular expression. It scoffs at the limits of language—the central drama of poetry—as an outdated concern of human consciousness. What use is there then for poetry, for mystery, for the pause that precedes a minor revelation?

SUPPOSE WE ARE in a crisis of mystery. People are hungry for context, itching for an explanation to everything they read, see, and encounter—even if the thing in question is a staged photograph of a blonde pop singer on her knees, “caught” in the act of fellating a (fully clothed) man. Recently, I was sent a study from Nature.com that declared, “AI-generated poetry is indistinguishable from human-written poetry and is rated more favorably.” The researchers concluded that “people rate AI poems more highly across all metrics in part because they find AI poems more straightforward. AI-generated poems in our study are generally more accessible than the human-authored poems [as] participants use variations of the phrase ‘doesn’t make sense’ for human-authored poems more often than they do for AI-generated poems when explaining their responses.”

AI-generated poems are not yet technically better than human poetry, although they may very well soon be. But in spite of their deficiencies, these poems are perceived by the non-poetry-reading public as being more understandable and therefore “more human,” due to “a misinterpretation of the readers’ own preferences.” It’s curious that the average reader conflates “sense” with human authority and “nonsense” with AI. Why must poetry make sense? What does it mean, after all, to make sense?

“The poet’s truth is also the desired truth of the other, whereas, precisely, the truth of a computer system is closed back upon its own sufficient logic,” writes Édouard Glissant in Poetics of Relation (1990). The modernists wanted to convey a sense of linguistic totality/multiplicity in their works, aspiring towards a comprehensive “truth of the other.” Joyce’s Finnegans Wake has been interpreted as a guide to modern media, capturing “a tremendous study of the action of all media upon the human psyche and sensorium” (McLuhan). Large language models were built with a similar aspiration in mind. Glissant presents us with an imaginary computer scientist who claims “that his machine, better than any other possible, sets us to thinking of totality.” But the machine’s version of totality (“a code totality”) is ultimately lacking. “It evades the drama of language,” Glissant writes, found in something like Eliot’s The Waste Land or Finnegans Wake.

In her essay “On Beginnings,” Mary Ruefle (quoting the poet Ralph Angel) describes “the poem [as] an interpretation of weird theatrical shit … Theater requires that you draw a circle around the action and observe it from outside the circle.” What Ruefle and Angel are describing is a social relationship (the self interacting with the world). Poetry, by this logic, is enacted through the observation of social relations from a distance, from “outside the circle” where the poet stands.

I’m reminded of a conversation between the poet Bianca Stone and the critic Ryan Ruby, where Ruby talks about poetry as the original media technology. Echoing the thesis he put forth in Context Collapse, Ruby argues that poetry is foremostly a social relation, not just a set of forms that produces an object on the page. According to Ruby, AI poses a threat to the project of poetry because language models “can operate in a world in which there is no audience.” And LLMs don’t “write” with a reader in mind, which is one of the defining characteristics of poetry as a response to the world. Instead, a simulacra/semantic average of a poem can be generated, based on pre-existing forms. The result is something that looks like a poem and sounds like a poem. The popular saying would have us believe that the thing in question is a poem. Hence the interest in having AI produce party-trick poetry after the style of Seamus Heaney or Sylvia Plath or whomever else. But the emphasis on distinction might be a red herring from a greater question. “We really have lost a consensus as to what poetry is,” Ruby says. “And that relates to our loss of the sense of the centrality of poetry to our society.”

It was interesting to hear Stone and Ruby struggle to define poetry’s function, even after recording a two-hour podcast on its history. Stone mentions that she recently heard someone describe poetry as “radical intimacy,” a characterization that briefly angered her. “I sense distance [is also] important,” Stone says. Indeed, I find in my favorite poems this paradox of distance and intimacy. Maybe distance cultivates intimacy between speaker and listener, between sublingual meaning and literal interpretation. Or maybe we treasure poetic expression because distance can never truly be overcome. AI can collapse the distance between thought and speech, but the machine, in its totality, cannot fathom the dramatic gulf within ourselves, which we try to resolve, again and again, through writing.

***

Love whenever your name pops up in the inbox : ) Great once again. I finished Byung-Chul Han's "The Scent of Time" the other day and it speaks on some similiar things you've brought up here. I think you might enjoy it x

"Why must poetry make sense? What does it mean, after all, to make sense?"

In the Spell of the Sensuous, David Abram writes: "To make sense is to enliven the senses. A story that makes sense is one that stirs the senses from their slumber, one that opens the eyes and the ears to their real surroundings, tuning the tongue to the actual tastes in the air and sending chills of recognition along the surface of the skin. To make sense is to release the body from the constraints imposed by outworn ways of speaking, and hence to renew and rejuvenate one's felt awareness of the world. It is to make the senses wake up to where they are.”

And that feels so appropriate to this essay and this quagmire we find ourselves in, where we're using AI to simplify or clarify or optimise in a world in which we've been robbed of the time to ponder and wonder and sense. AI cannot make the sense that Abram defines, which is affirming and freeing and orienting. I don't know if I have a point or a place to go, but I suspect I don't need one x