Copy and paste

An annotated syllabus...

A few months ago, the folks at Syllabus Project asked me to submit a syllabus on any topic of my choosing. After combing through some old notes, I decided to construct a syllabus exploring the concept of “intertextuality,” a term coined by the philosopher Julia Kristeva, in her 1980 essay “Word, Dialogue, and Novel.” Intertextuality supposes that there is a relationship between the text and all other literary works that precede it; a novel, for instance, exists in dialogue with the social and cultural environment that it’s published in. It seemed fitting, then, to compile a syllabus comprising mostly of citations, which I titled On the Wor(l)d as Collage, or Intertextuality.

The syllabus begins with a quote from the poet Alice Notley in her essay on “The Poetics of Disobedience.” Notley is challenging to categorize as a poet because she is so stylistically innovative and thematically opaque. Yet I find that her poems, no matter how surrealist or fragmented, always manage to retain a thread of emotional lucidity. Notley, too, is obsessed with the notion of voice on the page and the slippery nature of a writer’s selfhood, conveyed via the first-person “I.” Throughout her career, her work has remained distinctly polyphonic, peppered with overheard phrases, urban dialogue, and remarks from family, friends, strangers, and deceased loved ones. “The Poetics of Disobedience” is a manifesto, one that is, at times, ambiguous in the poet’s refusal to define herself. Nevertheless, I love Notley’s ambivalence towards words, the raw material of every writer’s work:

In an earlier draft, I opened with a line from the Bible, which felt too clichéd to keep in. But consider the parallels between what Notley writes about language (“I have a sense that there has been language from the beginning,”) and the biblical reverence of God as language, or the Word: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God … And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us, (and we beheld his glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father,) full of grace and truth.” Fascinating to think, too, how the Bible was a collaboratively written work that is revered as the Word of God, the Truth. If God is language, then the writer is the mere vessel for His message. This stands in direct contradiction to the public-facing nature of authorship today. (I’m sure there is a Simone Weil passage relevant to this somewhere, but I have yet to start reading her. Mystics, I believe, should be read in the wintertime.) I’ve been reading Dan Sinykin’s Big Fiction, an investigation into how conglomeration changed the publishing industry and American literature. It examines how the notion of singular authorship — authorship as a brand, so to speak (related to this NYT article on literary baseball hats, which I’m quoted in) — is ultimately contrived: “The published author channels the norms of a cultural system, its sense of literary value. She forges a commodity that will appear attractive to scouts, agents, editors, marketers, publicists, sales staff, booksellers, critics, and readers.”

It is humbling to consider writing as collage. As I’ve begun to write longer, more complex pieces of criticism, which often refer to a primary text (or various texts/sources), the process of writing increasingly feels like harvesting. I am harvesting language, “twenty-six abstract symbols that mean absolutely nothing,” and am tasked with organizing words, these structural units of thought, into sentences, into sense. There is freedom in approaching language like a crumpled dollar bill, continuously used in circulation. And sometimes, if you’re lucky, a readymade poem might materialize out of thin air.

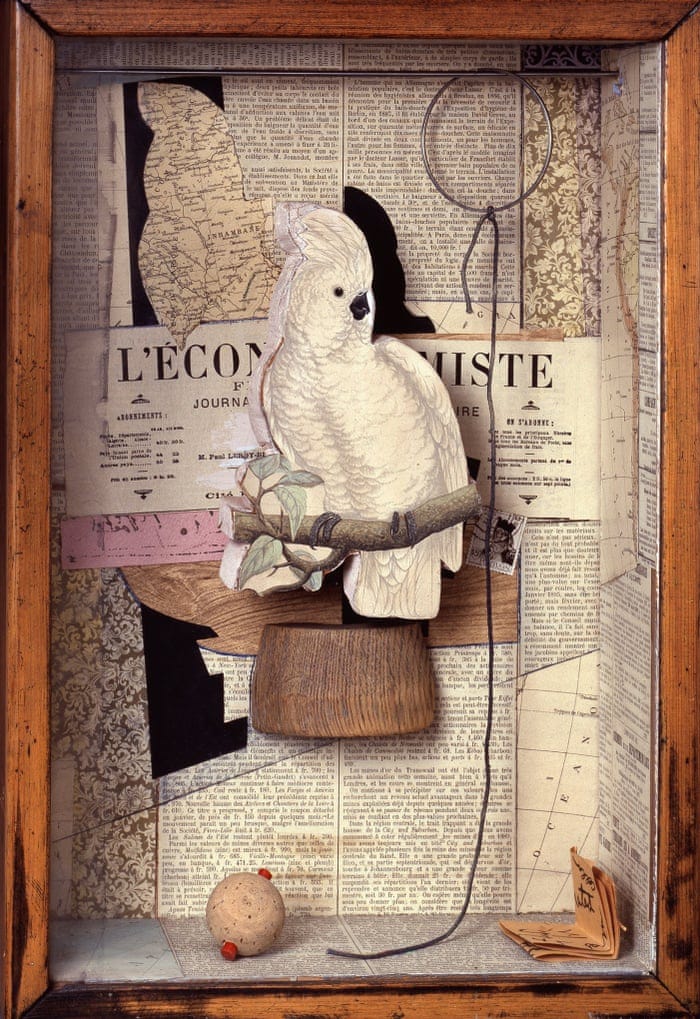

I mention many poets in this syllabus but only one artist: Joseph Cornell, whose collages I admittedly have yet to see in person. As Joseph Cornell did it, the world can be safekept in a box, enclosed but alive in composition within the bounds of enclosure. (This first clause I borrowed, of course, from John Ashbery: “As Parmigianino did it.”) It feels a bit meta to witness Cornell’s box-collages through the box of my screen; the images feel doubly enclosed, in a sense, doubly removed from their “natural” environments. And yet, Cornell’s mixed media assemblages elevate the individual mundanity of a readymade item, a news clipping, or a photograph beyond its original context. A parrot, cut from a page of TIME or LIFE or Nature Journal, becomes the centerpiece of a thematically-organized landscape. In collage, context matters. Left on a desk or lost in the trash, the same objects might appear forlorn, dejected, devoid of meaning. But when framed and composed with Cornell’s aloof elegance, a marble, a beaded necklace, a piece of string achieves its discerning aura as art, elevated from the matte mundanity of daily living.

Last year during Thanksgiving, that empty time-capsule of a week, I read Bernadette Meyer and wondered if I should spend a day attempting to write a book-length poem, as she had done with Midwinter Day. When everything written down becomes worth publishing because it is evidence of that day, that time. Whenever I experience “writer’s block,” I return to Meyer’s list of poetic experiments, which play with language as material to be repurposed. Craft, I think, can be discerned through uninhibited word-play, through the “systematic derangement” of a work’s possibility:

Below is the complete list of sources cited in my syllabus, which was an attempt at steeping the reader into a mood of language composed of multiple voices aside from my own!

1 “The Poetics of Disobedience,” Alice Notley, 1998.

2 Speedboat, Renata Adler, 1976.

3 “The AI Reader,” Terry Nguyen, Dirt, 2023.

4 “Poetry and Grammar,” Gertrude Stein, Lectures in America, 1985.

5 “Unhinged Articulation,” Ralph Angel, Número Cinq, 2013.

6 “Someone Is Writing A Poem,” Adrienne Rich, 1993.

7 “My Typographies,” Paul Elliman.

8 “Cybernetics and Ghosts,” Italo Calvino, 1967.

9 “Word, Dialogue, and Novel,” Julia Kristeva, 1980.

10 “Notes on the Nature of Joseph Cornell,” John Coplans, Artforum, 1963.

11 Three Conversations with Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Laura Hinton, Jacket Interview, 2003.

12 “Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” John Ashbery, 1975.

13 Experiments List, Bernadette Mayer, L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E #3, 1978.

Finally, some recommendations for a rainy weekend:

Lessons from Louise Glück (The Nation)

Indigo de Souza’s Tiny Desk performance. “Boys” is the perfect fall song.

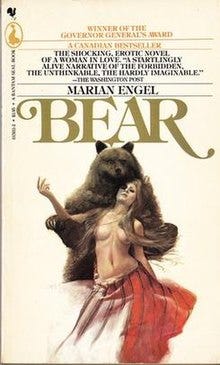

I enjoyed this Patricia Lockwood write-up of Marian Engel’s Bear. The old cover was definitely better.

As an unmarried woman, I have been reading a lot about divorce as of late… Finished Rachel Cusk’s Outline last month and more recently, Divorcing by Susan Taubes, for which the original title was To America and Back In A Coffin. Taubes was my favorite of the two.

Evan has a short story out in Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly called “There, There.” Not to be confused with the Tommy Orange novel of the same name… This narrator is engaged in a “parrot-husband cold war.” Perhaps I am biased, but it is very funny! You can get a digital copy of the issue for $9.99.

I particularly liked the paragraph that starts with “It is humbling to consider writing as collage.” You then speak of writing as harvesting and again as a crumpled dollar bill. It made me think of my short-lived venture into teaching creative writing, which I called “story sculpture,” yet another metaphor that fit me perfectly at the time. I still use it, feeling like editing out words is like trimming clay off a sculpture, or sawing off part of a papier-mâché that doesn’t work.