Cloud Time

Notes on "working for myself."

All installments of gen yeet will be partially paywalled since I have gone freelance! Subscribers will receive twice-monthly posts, including excerpts from in-progress essays, reviews, miscellaneous writings, and my personal journal.

If you can’t afford to subscribe, email me and I can a) comp a subscription or b) share individual posts. If you’d rather donate to me directly (Substack takes 10% of subscription revenue), you can Paypal or Venmo with your email, and I’ll add you to the subscriber list.

On Coney Island one afternoon, I tell Evan, “I understand now. We’re like clouds.”

He looks at me like he doesn’t understand, so I clarify: The self and its accompanying mental states are fleeting. Some moods hurry past us like unfurling clouds, racing towards a neighboring patch of sky. Others linger, drifting interminably like buoys in the bay. The sky is ever-changing, just like us. I point to a cloud, as if to prove a point. “You’re right,” he says, lying back.

On the beach, the clouds are our clocks, keeping time with the sun.

Now that I “work for myself” as a freelancer, I think a lot about time. My time is my own. I have no boss, no corporate overlord dictating the flow of my days. Every person’s time is indeed their own, but most people are forced to operate under constraints, making sacrifices so that, in exchange for time, they might have more money, more freedom, more security, more fun.

Every time I’m asked to quote my hourly rate, I’m reminded of the age-old adage, “Time is money.” Time is money, but in my line of work, I measure time in accordance with word count, thought, breath, even joy — which, to me, are the essential raw materials that make up a life. It is, however, in capitalism’s best interests that we forget everything save for the money, because if we start equating time with, say, leisure and not work, then time, as a metric of measurement, will have lost all sense of its profitable urgency.

It’s no wonder that writers have a famously poor grasp of time. “Whenever the writer writes, it’s always three o’clock in the morning, it’s always three or four or five o’clock in the morning in his head,” observes Joy Williams in an essay on writing. “Those horrid hours are the writer’s days and nights when he is writing.” A short story could take months; a novel could take weeks. For Marguerite Duras, dusk signifies the beginning of work, even though she claims to write every morning, but never according to a fixed schedule. “I’ve always experienced [dusk] not as the moment when work ends, but when it begins. A sort of reversal of natural values by the writer.”

According to the philosopher Byung Chul Han, who believes we are living in a modern time-crisis, narration gives time its scent. “Time starts to become olfactory when it obtains duration, when it obtains narrative tension or in-depth tension [by growing] in depth and width, in space.” Since the Enlightenment, Han argues, our understanding of time has been defined by progress. This sense of time, which he dubs historical time, “has the shape of a line, which runs or flies towards a goal.” It does not allow for lingering, the en media res state in which all writers work.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about novels that are entirely unhinged from historical, linear time, which may be the best examples of the narrative tension that Han references. Thuan’s Chinatown, Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights, and various Thomas Bernhard novels (which E. recommends) unfurl over the span of a given day (or event) within the narrator’s mind/memory; these works rely on the plasticity of time. For the insomniac (Sleepless Nights) or the trapped train passenger (Chinatown), linear time becomes wholly irrelevant when entering the realm of pure thought and memory.

In June, I interviewed Sophia Giovannitti, a writer, conceptual artist, and sex worker, about her recent essay collection Working Girl and performance work Dirty Calculations. Giovannitti argues that it’s impossible for art and desire to operate independently of capitalism, even if we try our best to refuse commodification. She has seen firsthand how this refusal—for the sake of artistic purity—can ruin a person’s creative practice: Her father was a diligent artist, who worked 60-hour weeks in construction while spending his nights making art in his basement. He maintained this practice for 50 years, and never sold a single piece.

Even so, “his art also remained touched by capital in every way, regardless of its refusal to willingly enter the market: flattened into the only pockets of time he could steal from his relentless schedule; restricted by which materials he could afford; abandoned at a few low points, in his exhaustion, but always returned to; tended to with verve up and against every obstacle.” Giovannitti points out the fallacy—and failures—of distinguishing between leisure and work time. Work, she argues, will always take up more of our time, energy, and resources, while our private pleasures remain an afterthought, pursued at our “leisure” in the dark hours of the night.

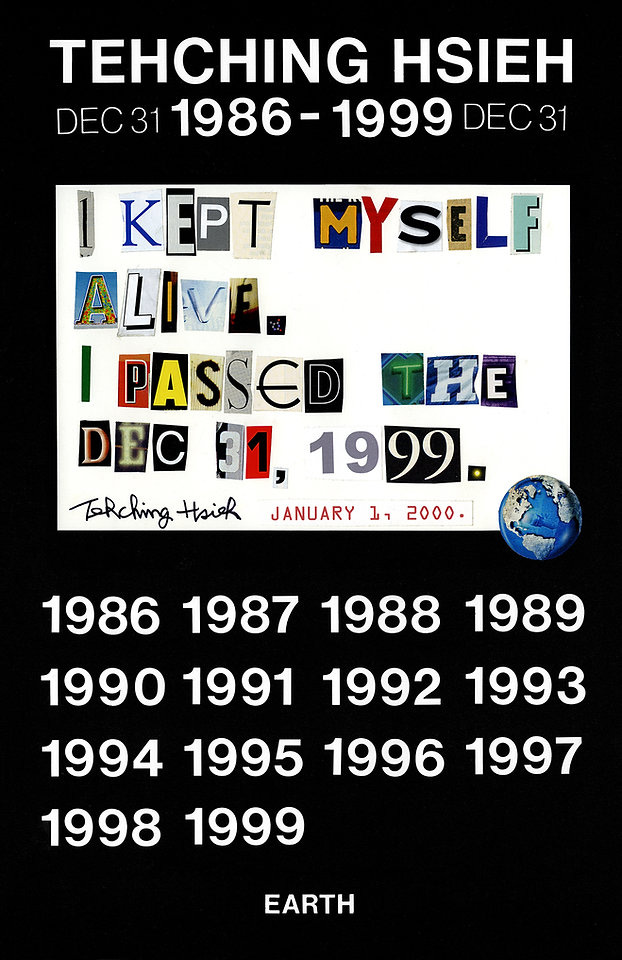

I thought of Giovannitti’s book while reading Lisa Hsiao Chen’s novel Activities of Daily Living (2022). It follows Alice, a freelance video editor, who is working on a side project about Tehching Hsieh while caring for her senile father. Though the book is fictional, Hsieh is a real Taiwanese-born performance artist living in New York. Time is Hsieh’s primary raw material, second only to his body. From 1978 to 1986, he committed himself to completing five one-year performances. These durational works had a simple, albeit baffling premise, like staying inside his studio for a year (Cage Piece), tying himself to a stranger for a year (Rope Piece), or punching a clock every hour for a year (Time Clock Piece).

When asked about the meaning of these performances, Hsieh has responded with Zen-like mystique: “Life is a life sentence. Life is passing time. Life is freethinking.”

Like Giovannitti, Hsieh does not distinguish between time well-spent and time, well, spent. There is no distinction between art-time, work-time, or leisure-time, as Hsieh’s performances are all-encompassing, which requires him to be immersed in the present. To him, it all adds up to a life—a lifetime of living.

For Alice, projects help structure her time as a freelancer by imbuing it with purpose, even though she has no idea how exactly her nebulous project will take shape. (Alice appears to be the fictional stand-in for Chen, who’s admitted to her longstanding obsession with Hsieh.) All she knows is that it will take some time.

For the past year or so, I’ve told friends, acquaintances, and prospective agents that I am obliquely “working on a book.” More often than not, several months have gone by without me writing or even thinking about the book; some weeks, I’m content with bookmarking an article that is somewhat topically related to my research, though, as any writer knows, you can never really prepare yourself for what you are going to write. I have, of course, felt guilty about this. I also feel guilty about locking myself up in my room and wasting my youth, but I have since come to approach my book with renewed purpose. I obsess over its potential like that of a new lover. Everything I do is in service of the project. Perhaps that is the secret to writing a book.

The narrator in Sleepless Nights muses that time “is something else,” something murky and indistinct for “the hesitant intellectual,” for whom “years fly by like a day; life is shortened by the yellowing incompletes.” The intellectual’s project is akin to “a plaguing growth that does not itself grow, but attaches, hangs on, a tumorous companion made up of the deranged cells of learning, experience, thinking.”

In 1986, Hsieh announced that he will embark on a 13-year project. He will privately make art during this period, but not show it to anybody. What did he do during this time? Hsieh: I kept myself alive.

We drift in and out of sleep watching Derek Jarman’s Blue, an abstract film with only one image. The monochromatic blue, generated from a wavelength of light in a film laboratory, is cut by four thin sky-blue lines on the secondhand TV. Given this static visual, Blue is better described as a sound piece, an image-less compilation of speech, natural euphony, and ambient noise. During its production, Jarman was losing his sight to complications from HIV/AIDS, though he has long toyed with abstraction in his art. Parts of the script hint at Jarman’s artistic hostility towards image, figuration, and narrative rationality, as the order of images in a moving picture (a problem that Blue skirts by its abstraction) threatens to impose an order upon the fictional film world.

“The image is a prison of the soul,” Jarman writes, while pure color is “the fathomless blue of bliss.” He continues: “To be an astronaut of the void, leave the comfortable house that imprisons you with reassurance.” I interpret this as an instruction from Jarman: Leave the comfortable house of narrative and visual order to strive towards the mystical void, the light. But our search for/of light is limited, he reminds us, as “time is what keeps the light from reaching us.” Like us, light is also constrained by time.

Blue, I suppose, can be listened to like a podcast (it was broadcasted on BBC Radio upon its release) while completing chores or commuting, the soundscape compressed into life’s background for easy consumption. But there’s a charm to seeing Blue in reverie while one’s consciousness hovers in a drowsy, fluid state.

The sensation reminds me of an early passage from Proust’s In Search of Lost Time: “When I awoke in the middle of the night, I did not know where I was, not even, at first, who I was … but then memory came, as from above, to pull me from the nothingness, from which I could not have helped myself; within a second I went through centuries of civilization, and from vague images of petroleum lamps and shirts with open collars, my self gradually assembled anew in its original shape.”

Jarman was interested in inducing a meditative state upon audiences. Blue begins and closes with the ringing of Tibetan bells perhaps so that, for the duration of the film, our selves can be assembled anew in half-sleep. Towards the end of Blue, we hear the sea. Brian Eno’s voice lulls us towards a crisp image of a lover: “Dead good looking / in beauty’s summer / His blue jeans / around his ankles.” The memory arrives like a dream to pull us from the nothingness, only the voice dismisses it seconds later.

“Our name will be forgotten / In time / No one will remember our work / Our life will pass like the traces of a cloud.”

I was, at that point, awake enough to cry.

If no one will remember our work, I ask E., what is the point of it all? (I forgot his response, as did he, since we were both stoned.) We do the work for the work, he later tells me. Perhaps it’s not worth overthinking. We do the work to elevate the ordinary into plot, to find an imperfect order for things where there is none.

Sometimes when I begin to read your work I feel like I am being blindfolded, taken by the hand, and led someplace I have never been. Then the piece ends and I lift my head and look around at a slightly different world.