“We are born with a scream; we come into life with a scream, and maybe love is a mosquito net between the fear of living and the fear of death.” —Francis Bacon

I. Silence

ON THE AMTRAK, the quiet car is a relief, silence being the sole code of conduct agreed upon entry. Not stifling but earnest quiet, like that of a library, upheld by a shared understanding, a solidarity between passengers. I read most of Clarice Lispector’s An Apprenticeship or The Book of Pleasures held by this silence. Between chapters, I rested my head against the window, my vision sharpened by the winter sun. My mind took respite in the page breaks. Lispector’s narration into the psyche of Lóri, a reserved schoolteacher on a spiritual quest of self-discovery, oscillates between intense rumination, digression, and dialogue. Reading her is like entering the mind of a person tranced in prayer. Lispector requires you to surrender to her shifting tides, to leave no room for thought, reason, or doubt.

Most of the book is a dialogue between Lóri and “the God” inside her, as she prepares for a mystical transformation that will, in due time, allow her to consummate her platonic relationship with Ulisses, a philosophy teacher she burns with desire for. They meet by chance on a street corner; Ulisses approaches Lóri, believing they are fated to be lovers, but not until she is ready for it. What is it? Lóri does not know, but she knows “Ulisses’s human condition [is] greater than hers,” and so she follows his opaque lead. Similarly, there is comfort in reading Lispector because her human condition is greater than mine. I have been a blank slate since November. Somehow I managed to apply to various MFA programs between then and now. Yet I remain gripped by silence, the kind that renders you discontinuous, cleaved in two. I felt incapable of synthesizing old memories, new experiences, and current events into anything formal, whole, comprehensible. Call it a failure of narrative memory. It is January, I thought, so I am allowed to be dramatic.

Lóri writes Ulisses letters and he, in return, calls her. In one letter, Lóri writes of a holy silence, “the silence inside us” that quickens the heart and is found “in the very heart of a word.” She writes: “For if at first the silence seems to expect a reply—what an urge, Ulisses, to be called and to respond; soon you discover that it demands nothing of you, perhaps only your silence.” I want to accept the silence, but my instinct is refusal. It feels punishing—not holy, but necessary. I try to assure myself: Perhaps the point is to dwell in its negative presence, as Lóri does, marveling at how “intransmissible” humans are, despite our gestures and words. How to find hope in that intransmissibility, to not let it reduce me to despair or fear.

II. Violence

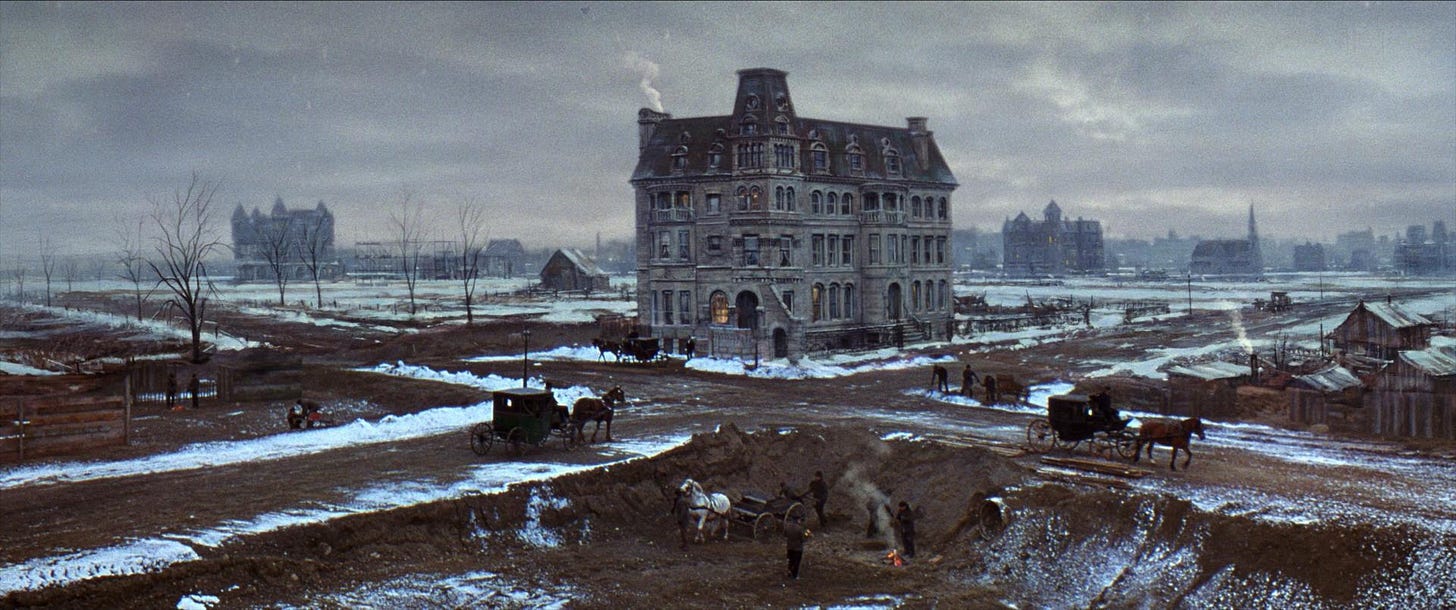

SCORSESE CALLS The Age of Innocence (1993) his most violent film. The period drama was made between Goodfellas and Casino, but I’d hardly consider it a palate cleanser despite its stylish restraint. No characters are killed, maimed, ambushed, or even threatened, but there’s a repressive brutality to Wharton’s social order that, for Scorsese, is analogous to the modern mafia’s inner workings. The film’s violence is subtly enacted upon Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis), who is paralyzed by his own complicity.

While on the train to New York from Boston, Archer senses that he is a foreigner among his fellow travelers, estranged by his illicit affections for Madame Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer), his not-quite mistress and not-quite lover: “He had a feeling that if he spoke … they would not understand what he was saying.” Here, silence is the double bind that preserves the affair as an artifact of Archer’s fantasy. It, too, is the sharp knife that rules over society’s state of affairs. Its members abide by an unyielding, unspoken code that leaves no room for dissent, and Archer does not dare give voice to any disagreeable thoughts or opinions.

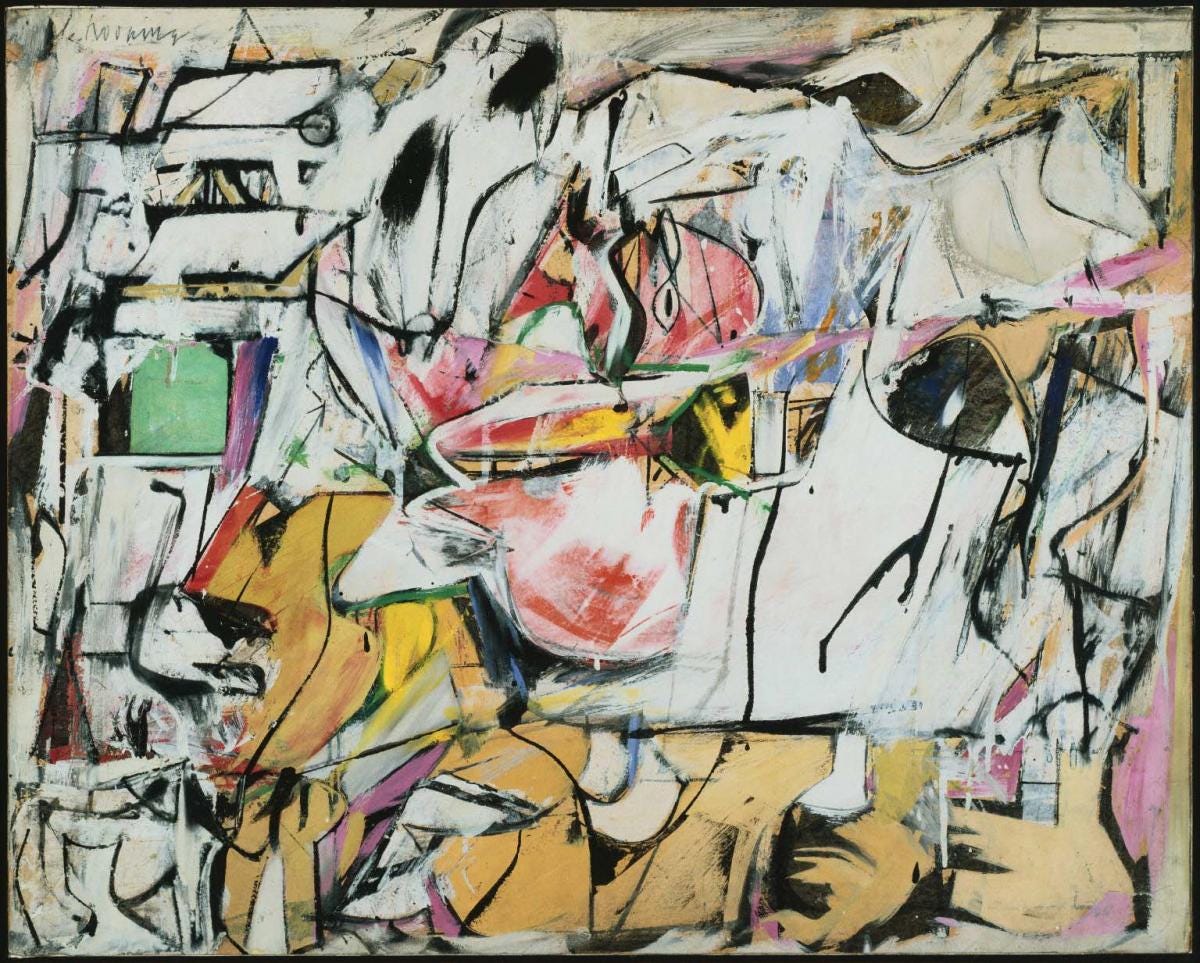

It’s tempting to abstract the violence of Wharton’s drama, to dismiss its upper-class fixations as too narrow or anachronistic for our times. But there’s a monstrosity to its machinations that I can’t turn away from. Perhaps because The Age of Innocence is a wintry, violent novel and we are living through wintry, violent times (even the Los Angeles fires feel wintry in their self-immolating rapture), and there are parallels in Wharton’s incisive cruelty to our drably unquantifiable state of affairs—how cruel indifference can be exhibited through affect, beyond purely explicit action; how such affective violence can paralyze one’s spirit to irredeemable depths, like the bitter chill that was settling over DC and the rest of the Northeast. Suppose my fear is unwarranted, even exaggerated, but January thrummed with an amorphous violence. From the corner of your eye, its menace lingers, like the Willem de Kooning painting tucked away on a stairwell that antagonizes you with its chaos.

Tuesday night, walking down Q St, marveling at the quaintness of the snow-studded townhouses, I forget that I am but a few miles from the historical landmarks, barren symbols of the state’s monopoly on violence. No matter the president, the ruling party, the landmarks stand illuminated, stark in their certainty. On every election night, the networks broadcast the Washington Monument as a kind of solemn screensaver. Its tapered neck recalls a chipping hammer, a tool that would soon be taken to the neck of democracy.

When I lived in DC, I would snake my runs around the National Mall to revel in the grandiosity. In my chest was a swelling of self-importance, a sign that I was close to the country’s pulse. I felt there was purpose in documenting the discourse, the center of the storm. I do not miss that narrow-mindedness. On long gloveless walks around the Capitol, the wind seared my hands salmon-pink. I resigned myself to bearing the elemental brunt until it became unbearable. I had to duck inside a coffee shop to defrost. Gripping a drip as a hand-warmer, I felt suddenly betrayed by my passivity, this minor act of self-inflicted violence.

Scene report after scene report of inauguration week soireés: I felt incapable of tolerating writing that reads as ideologically barren, loyal only to visibility and transgressive posturing. Somehow worse than cruel indifference, it signals an allegiance to an aesthetics of cruelty, a cowardice that feigns cruelty without ever accounting for its real ramifications. The cowardice negates something, but never the cruelty. If you plan on swinging your fist, at least land the punch. This “new” era is simply a cataclysmic continuation of the old ways of being. What will it take to wrench us from its deadening grip, to stir us towards something akin to action?

III. Reality

IN EARLY JANUARY, I attended a screening of an indie film that followed two conspiracy theorists, men who become so possessed by paranoia that they lose touch with reality. The film is shot like a post-apocalyptic thriller, an approach that compels the audience to suspend their attachment to “reality,” convincing us that the characters’ beliefs and fears are warranted. We meet them not as conspiracy theorists, but heroic survivors of a post-apocalyptic world. The film’s ending is a rug-pull that subverts this framework, exposing the extent of the men’s delusions. Its message is not a warning, but an observation: Reality is fraying at the seams. An accelerating sense of disorder prevails. In Dean Kissick’s excoriation of identity politics and its role in “ruining” contemporary art, he adopts a resignedly earnest posture on the end of “consensus reality” as a kind of flashpoint that art should seize upon:

“We are blessed to live now, in the West, in a strange world without common sense. As fact grows stranger than fiction, we should embrace the surreal and try harder to imagine more outlandish fictions. We might begin by accepting that we are being lied to all the time, that most of what we hear and see is an illusion, misrepresentation, or performance—and that’s fine. Life has in many ways become a fiction, reality is vanishing under its own representations, we are suffering from collective delusions, we are teetering on the precipice of the real, with a multiverse of fantasies spinning out beneath us—and that’s okay, that’s fine. Reality is gone, and the art crowd keeps trying to recover it, keeps claiming, “Oh, we can find it again, we can hold on to it, if we just keep exhibiting ceramics, if we just keep making paintings”—but we cannot!”

I assume Kissick is referring to the proliferation of general artificial intelligence and the ever-confining chambers of our social media feeds, boxing us into algorithmically-predetermined versions of reality. The hyperreal and so forth, as predicted by Baudrillard. Yet I reject the cynicism of his acquiescence. Recovering a sense of integrated “reality” might be impossible, but wholly disengaging with its cruelty in favor of delusion is, for lack of a better word, irresponsible. Fantasy is a realm available only to those are “blessed to live now, in the West,” and even then there are caveats between the blue-chip artist and the service worker, the naturalized citizen and the undocumented immigrant. Without a consensus reality, there can be no collective fantasy—the American dream receding from sight in the rearview window.

Beyond reality, Kissick implies, is the sublime, but what does the sublime have to offer us now? A painting by William Turner does not engender the same degree of awe in 2025 as it did in 1856. Simon Critchley leveraged a smarter critique against contemporary art in 2012, proposing a turn towards the uncontainable, the monstrous, to reckon with the unbearable nature of reality. If reality is unbearable in its cruelty or falseness, art should enact a “certain semi-autonomous distance from the circuits of capture and commodification” by being irreconcilable with existing norms. Art should trigger an “abject” response: shock, disgust, confusion, fear. Piss Christ comes to mind here, as do the paintings of Francis Bacon—works that “deploy the essential violence of art, and perhaps understand art as violence against the violence of reality, a violence that presses back against the violence of reality, which is perhaps the artistic task, thinking of Hamlet, in a state that is rotten and in a time that is out of joint.”

Last summer, I left ten minutes into Arthur Jafa’s revisionist “Taxi Driver,” a 73-minute “film” that repurposes footage from the most gruesome scene in Scorsese’s movie to play on loop. In Jafa’s remake, the pimp is Black, not white, a revision based on Paul Schrader’s original script (Scorsese ended up casting a white man for the role, fearing audience protests). I couldn’t bear the unrelenting violence. I looked at my phone. I scrolled, texted, and stood up. It didn’t matter whether Jafa’s remake had critical merit; I was too distressed by the brutality on repeat. Perhaps the point was that, up to a certain point, violence becomes too relentless to fathom. Can aversion be its own kind of confrontation when the rottenness is too much to bear?

IV. Identity

THE LAST LYNCH MOVIE I saw before his death was Lost Highway. Two stories, two men: Fred, a jazz musician, is tortured by suspicions that his wife Renee is having an affair. Paul, a mechanic, is seduced by Alice, a mobster’s beautiful mistress. In true Lynchian fashion, Patricia Arquette plays both the wife and the mistress, donning a blonde wig as the latter. The narratives overlap, glitch, and deteriorate into nightmare, revealing the fractured nature of Fred’s psyche after he is accused of murdering Renee. A woman is never safe in Lynch’s world, but her violation is rarely the stuff of spectacle. Some might disagree, but Lynch’s inclination towards violence never seems gratuitous or masturbatory. Discomfiting, yes, in the most sinister scenes, but his work masterfully toes the line of the unbearable. Phillippa Snow wrote it best:

“Performative femininity, and the actress as a metonym for womankind; doubledness and doppelgangers; the uneasy commingling of violence and sex, sometimes in ways that were deathly, and sometimes in ways that were erotic… For me, [Lynch’s] endless return to the well of male sexual violence never seemed approving, only disbelieving, as if he were circling back to the crime scene of the American Dream to try and come to terms with the perpetual, sinister containment of this particular evil inside it.”

How to describe Lynch’s lurid dreaminess? When a daydream shifts into the minor register of a nightmare. The imitators can invoke his color palette, cast off-beat archetypes to mimic a mood, but no one comes close to wading through his phrenic, primal muck. “When characters are sufficiently developed and human to evoke our empathy, it tends to break down the carapace of distance and detachment in Lynch, and at the same time it makes the movies creepier—we're way more easily disturbed when a disturbing movie has characters in whom we can see parts of ourselves,” writes David Foster Wallace on Lost Highway.

At the core of Lynch’s work—and his most memorable characters—is the gruesome, irreconcilable nature of the self, or identity. In the “fascination with identity” that Kissick denounces, beyond the desire for recognition, there is an itch for context: How have I become who I am? Why am I perceived this way by society? How does the artist/viewer situate themselves in relation to the past, present, and future? Lynch’s films seek to expose the uneasy dualities inherent in us all; he refuses to present us with fully integrated characters, giving us bits and pieces of their rage, anxiety, and sexuality. His characters are often in crisis, struggling to maintain a coherent grip on reality—which impacts how they perceive their own identity, their role in the story: Is Mulholland Drive’s Diane Selwyn (Naomi Watts) a rising Hollywood starlet or a discarded hanger-on, still hung up on her successful lesbian lover? In Lost Highway, which aspects of Fred’s narrative are real, forgotten, and/or imagined? Does Fred dream up an alternate reality where he is Pete, a young mechanic capable of sexually satisfying his wife, or is Pete a real person, roped into Fred’s nightmare?

Lynch hedges at the rotten disjointedness of the self that leads to conflict. “I like to remember things my own way,” says Fred. “Not necessarily the way they happened.” It is not just reality that is unbearable. Like Fred, I find my own self unbearable, and so I’m prompted to avert my gaze, remember differently, entertain conspiracy, dance with cruelty. The more I watch Lynch the less I’m sure about myself. There’s a sick displacement at play, mouths opening to swallow a silent scream.

***

This was so good. Thank you for this thoughtful, wise, and important critique of Kissick, and also just an immensely beautiful essay, in all of its movements, too.

Has Dean Kissick always been a slippery troll? His whole thing feels a little insincere